| THINK-ISRAEL |

| HOME | January-February 2009 Featured Stories | Background Information | News On The Web |

Part 1: A GERMAN POPE DISGRACES THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

Many knew that Richard Williamson was a notorious Holocaust denier. Pope Benedict XVI, who brought him back into the Catholic fold two weeks ago, did not. Many are now wondering whether the pope has lost touch with the world outside the Vatican walls.

Via Urbana is an alleyway of prostitutes and craftsmen, not far from the city's main train station and yet, like everything in Rome, so close to heaven. The words Regina angelorum ora pro nobis... ring out from the ground floor of No. 85 Via Urbana, a shop furnished with crystal chandeliers and damask wallpaper.

A group of devout Catholics meets here every Thursday, at 6:30 p.m. Its members consider themselves the keepers of eternal truth, and they feel flattered when berated for being more papal than the pope. Indeed, that is precisely what the ultra-religious members of the SSPX strive to be.

SSPX, which sounds some new piece of computer software, is in fact

an acronym for the "Fraternitas Sacerdotalis Sancti Pii X," or the

Society of Saint Pius X. It is home to the traditionalist followers of

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre.

These nine members of the SSPX, devotees of the old mass celebrated in Latin, are sitting or kneeling here, in their chapel of St. Catherine of Sienna. They include two matrons wearing little hats, three apostolic-looking teenagers and a girl wearing a veil. The priest stands with his back to the congregation.

There could be no greater contrast than between this archaic service in a 540-square-foot shop and the massive St. Peter's Basilica across the River Tiber. And yet last week, one of these guardians of a lost form of Catholicism drew the Vatican into a crisis that has seriously damaged relations between Catholics and Jews, and has even caused fractures within the Christian community itself. Indeed, it will be a while before its repercussions can be fully assessed.

Notorious Holocaust Denier

The decision by Pope Benedict XVI to reinstate the bishops of this brotherhood of St. Pius, who were excommunicated in 1988, has been the source of astonishment, disillusionment and outrage both inside and outside the Vatican. It has also triggered a deep sense of despair over the future relationship among religions. The fact that it was merely a matter of housekeeping within the church — the ultra-conservatives who were restored to the pope's good graces had been made bishops in unsanctioned consecrations by Lefebvre in 1988 — was irrelevant. What triggered the scandal, as SPIEGEL reported two weeks ago, was the fact that one of the priests brought back into the fold, Bishop Richard Williamson, is a notorious Holocaust denier.

During a visit to Germany only two weeks ago, the British cleric told Swedish television: "Not a single Jew died in a gas chamber." The 68-year-old Cambridge graduate then proceeded to talk about technically unsuitable chimney heights and poorly sealed doors at Auschwitz. When asked about his anti-Semitism, Williamson replied: "Anti-Semitism can only be bad if it is against the truth. But if something is true, it can't be bad. I am not interested in the word anti-Semitism."

And this obstinate priest, of all people, is to be reinstated into the church, according to the will of the pope?

With a single, perhaps imprudent gesture, Benedict XVI has reignited old fears among Jews the world over, fears that the Catholic Church has in fact never really shed its old anti-Semitism. Benedict has called into question the efforts of his predecessor, John Paul II, who was the first pope to apologize for the crimes of his church. And he has raised a concern among his supporters that the German pope could in fact be a pope of the Restoration, a man who is taking his church, which had cautiously stepped into the modern world, back into the ivory tower of theological dogma.

And then there is the question that has the entire world worried: How can it be that a German pope, of all people, is pardoning a Holocaust denier? Did the pope underestimate the impact of his gesture? Did Benedict XVI have a plan, or was his decision based on the occasionally obscure theological logic of the Vatican's clerical bureaucrats? Does the pope, a man of books throughout his life, still understand the world outside his palace walls?

'How Can a Liar Be Pardoned'

The decision has sparked outrage among Jews worldwide. The Israeli Chief Rabbinate promptly cut off its interfaith dialogue with the Vatican. Israeli Minister of Religious Affairs Yitzhak Cohen, referring to Israel's diplomatic relations with the Vatican, recommended "completely cutting off connections to a body in which Holocaust deniers and anti-Semites are members." A stunned Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, a survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp and Israel's former Chief Rabbi, asked: "How can such a liar be granted the protection and pardon of the leader of the Catholic Church?"

It is a question that many Catholics are asking themselves, especially in the pope's native Germany. "People here are simply dismayed," says Klaus Mertes, a Jesuit priest and rector of the Maria Regina Martyrium Church, a commemorative church for the victims of the Nazi era in Berlin's Charlottenburg neighborhood. This sense of outrage, he says, is reason enough to speak out on the incident. "There is outrage over Bishop Williamson, on the one hand, as well as over the decision coming from Rome. It may be that the reasons have not been communicated yet. But what, for heaven's sake, could those reasons be?"

Bishop Gerhard Müller of Regensburg, a traditionalist himself, criticized the pope for having "extended both hands to a marginal group" and banned Bishop Williamson, who "invented stories idiotically and scandalously," from all churches and facilities in his diocese.

In the northern city of Münster, where Joseph Ratzinger was once a theology professor, almost the entire Catholic faculty signed a sharply worded letter of protest and criticized the shift in the Vatican. Ferdinand Schuhmacher, the city's official representative of the Catholic Church, apologized publicly to the chairman of the local Christian-Jewish alliance, Sharon Fehr, for the pope's behavior: "No matter how hard I try, I cannot understand the pope's action."

Some German Catholics have already made their way to their local registry offices to officially leave the church. The mood among many is reflected in the succinct words of Helmut Reinhard, a 62-year-old Munich Catholic: "I've had it!"

Damaged Jewish-Catholic Relations

Fifteen members of his family were lost in Auschwitz-Birkenau. "They were all gypsies," he says, "and all Catholics." His cousin Markus Reinhard, 50, lives in Cologne. Last Tuesday, on Germany's Holocaust Remembrance Day, he, his wife and his four sisters left the Catholic Church.

Many others in the religious community began to vent their anger on the Internet early last week. The religious forums on Web sites like "myKath.de" have been inundated with comments. "As of last Saturday, who even takes excommunication seriously anymore?" asks one contributor to the forum. Another outraged Catholic writes: "Williamson is committing a crime in Germany (denial of the Holocaust), while his flock looks the other way and the pope rewards him by making him a bishop in the Catholic Church. What happens if Williamson sets off a bomb in a synagogue? Will the pope appoint him as a cardinal then?"

Even Heiner Geissler, a former general secretary of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU), regrets "that the pope is sealing himself off from women, people of other faiths, divorced people and homosexuals."

Just four years after the first German pope of the modern era took office, the relationship between two major world religions is shattered. The process of reconciliation between Catholics and Jews may have been damaged for years.

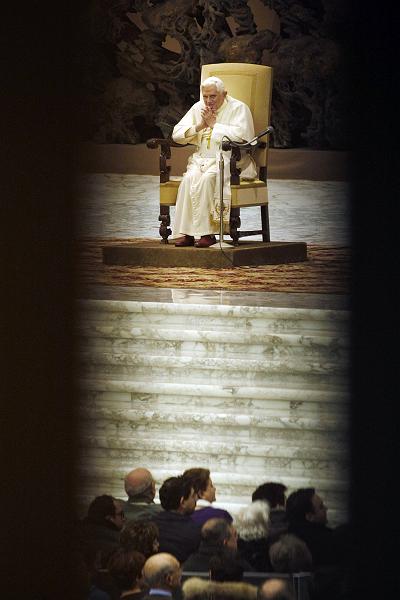

Of course, Benedict has done what he could to control the damage. In his Wednesday audience last week, he addressed the subject directly: "In these days, as we commemorate the Shoah, I remember the images of my repeated visits to Auschwitz (...) While I once again express, from the bottom of my heart, my full and indisputable solidarity with our brothers, the bearer of the first covenant, I hope that the memory of the Shoah moves humanity to reflect on the unpredictable power of evil when it conquers the human heart."

Despite the clarity of these words, the pope read them with barely perceptible conviction. And they did little to defuse the conflict. German Chancellor Angela Merkel dismissed the comments on Tuesday, saying that she expects more. "I do not believe sufficient clarification has been made," she said.

Indeed, until this week the pope seemed not to have recognized the scope of worldwide outrage. Now, though, the volume of protest seems to have reached a volume that has even managed to penetrate the Vatican's inner sanctum. On Wednesday, almost two weeks after the controversy began, the Vatican finally issued a statement demanding that Williamson, "in an absolutely unequivocal and public fashion," distance himself from his statements denying the Holocaust before he can be fully readmitted to the Church.

PART 2: A PONTIFF OF SLIP-UPS AND BLUNDERS

The Vatican also admitted that Pope Benedict XVI had been unaware of Williamson's views on the Holocaust when he revoked his excommunication. It is an admission that may ultimately defuse the present dispute. But it will do little to assuage Catholic fears that Pope Benedict XVI has a tenuous grasp on reality.

On April 25, 2005, when the man who was once Joseph Ratzinger greeted German pilgrims as Pope Benedict XVI for the first time, he confessed: "I said to the Lord, with deep conviction: Do not do this to me!"

His quick prayer was not heard, and there was enormous enthusiasm for the new pope at first, at least in Germany. Wir Sind Papst! (We Are Pope!), the tabloid Bild trumpeted in celebration of the career of the Bavarian theology professor, who, in his previous job as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for several years, had kept watch over the purity of the Church's teachings. But now there is growing skepticism over this pope's ability to discharge his office. Some of the sheep in his fold already fear that this erudite spiritual leader will go down in church history as a wrong choice, as a pontiff of slip-ups and blunders.

The pope, for his part, seems not the least bit concerned about the rapid vanishing of public enthusiasm. Ratzinger has always been suspicious of the adoration of the masses. He had deep misgivings about the pilgrimages young people made to hear his predecessor, John Paul II.

Falling Numbers

This may explain why he seems untroubled by the continuous decline in the numbers of pilgrims appearing on St. Peter's Square. Last year, 2.2 million people attended his Wednesday audiences, one million fewer than two years earlier. The anticipated recent awakening of his church has failed to materialize, which is another reason why there is so much disappointment over the pope's most recent decision.

Last week, Radio Vatican received a constant stream of furious e-mails. Some were read on the air. One listener wrote: "Shame on the Vatican, which supposedly knew nothing about the statements of Bishop Williamson. Pope John Paul II would have thrown out the people at the Vatican responsible for this."

Another wrote: "I am unspeakably furious with Mr. Ratzinger. The ground is being prepared for new pogroms here." A third listener of the radio station, which is broadcast internationally, even called upon the Vatican to convert the Holocaust denier and bishop "with a mandatory pilgrimage to Auschwitz." Yet another yearned for the days of Ratzinger's predecessor: "With the rehabilitation of the openly anti-Semitic Lefebvre priest, Benedict ridicules the legacy of his predecessor, who fought tirelessly for reconciliation between Christianity and Judaism."

Many in the pope's immediate surroundings are also dismayed about the new debate over anti-Semitism. Last week even the loyal Osservatore Romano sharply criticized the pope's handling of the matter. The paper wrote that it regretted that the repeal of the excommunication of the four St. Pius bishops was simply handled "according to the wrong script" at the Vatican.

Benedict decided to issue the decree lifting the excommunications without consulting with the relevant offices of the Curia. Vatican sources say that the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity was not consulted. "It was the pope's decision," German Cardinal Walter Kasper, the chairman of the council, explained. Kasper, a former companion of the pope now somewhat saddened by his friend, has since submitted his letter of resignation.

According to a member of the bishop's congregation charged with the matter, the decree, which was intended to reconcile the traditionalists with their church, was to be issued on the 50th anniversary of the decision to convene a second Vatican Council by reformer Pope John XXIII. That would have been on Jan. 25 — perfect for a historically-minded pope like Benedict XVI.

The pope, though, was apparently unaware of the fact that Jan. 27 was the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, and, as the Vatican has now admitted, he did not know that one of the rehabilitated bishops was a notorious Holocaust denier. And none of his close associates seemed to feel a need to enlighten him.

Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, the prefect of the Congregation for Bishops, signed the decree on Jan. 21, a Wednesday. But just a short time later, he apparently realized what he had done.

The papers were already filled with Williamson's views at the time.

The smart thing to do would have been to hold off with publication of

the decree. Italia Oggi, a business newspaper, cited witnesses

who claimed to have listened in on a fit of rage by Cardinal Re. "What

a bungler!" the witnesses say the cardinal shouted, as he sat in a bus

on a Sunday morning, on his way to mass at the Basilica of St. Paul

Outside the Walls. He was not referring to the Holy Father, but to one

of his fellow cardinals, Columbian Darío Castrillón Hoyos, who had

urged him to sign the decree.

In the wake of the slip-up, however, there was no efficient crisis management, not even in the Vatican Press Office. While Bishop Williamson's comments on the Holocaust were broadcast across the world, the press releases from the Holy See initially addressed the awarding of honorary citizenship to the pope by the German town of Mariazell and the communion of the Patriarch of Antioch.

It was not until mid-week that Vatican officials realized that a disaster had occurred. Aides quickly posted a few videos on YouTube, showing the pope's speech at Auschwitz, his visits to synagogues and amiable meetings with Jewish dignitaries. The YouTube site had received all of 1,900 clicks by Friday.

Did the Vatican even know about Williamson? "Here is the problem," Father Eberhard von Gemmingen, the head of Vatican Radio's German service, said in a commentary last week: "What exactly is meant by the term 'the Vatican?' The Vatican is large. It has many offices. Some offices that deal with politics were certainly familiar with his anti-Semitic statements. But perhaps these offices were not informed early enough that his excommunication was being revoked."

The second department of the Secretariat of State, which handles foreign relations, should also have concerned itself with the decree. "There must have been individuals there who knew Bishop Williamson. Tarcisio Bertone, as Cardinal Secretary of State, hovers above all agencies, and above him is the pope."

In other words, the explanations seem to indicate, it was all the result of sloppy work in the Roman Curia bureaucracy. If only it were that simple.

The slip-up involving the St. Pius bishops could not have turned into a scandal but for two, closely-related problems associated with this pontificate.

The first is the growing isolation of Benedict XVI. And the second is his trepidation when it comes to interacting with the modern world. It is a deeply conservative fundamental attitude, which repeatedly leads to "ecumenism to the right," as Johann Baptist Metz, a theologian and professor of fundamental theology, said recently in criticism of the pope.

The pope, says one member of the Curia, has surrounded himself with a team of yes-men, devoid of any critical voices. The team even shields the 81-year-old pontiff from unfavorable reports in the media. "As a rule," says the official, "he is only presented with excerpts from the international press. And in many cases, his staff members say: No, no, we cannot show him that article."

Unlike his predecessor Angelo Sodano, Cardinal Secretary of State

Bertone is considered relatively apolitical. Benedict appointed the

cardinal because he had shown himself to be "prudent in pastoral care," and because he was familiar with Bertone from their days serving together on the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

A conservative lobby has formed around the pope over the years, with considerable influence and abilities to manipulate policy. It includes the members of groups like Opus Dei, the Legion of Christ, the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter and the SSPX.

When it comes to rapprochement with other religions, they not only delay and debate ad nauseam pending decisions, but they also allow their views to leak to the outside world. One example was the pope's baptism of a Muslim during the Easter vigil mass in St. Peter's Basilica in 2008. The conservative lay movement "Comunione e Liberazione," which is highly influential in Italy, orchestrated the baptism.

The demonstrative conversion of a Muslim to Catholicism became an immediate source of indignation among Muslims around the world. Arab dailies wrote that the water that Pope Benedict had poured onto the head of the convert was "like petrol thrown onto the fire of the clash of cultures." At almost the same time, terrorist leader Osama bin-Laden broadcast on the Internet a message critical of the pope, accusing him of playing a key role in a new crusade against Islam.

Minor acts, fleshed out in the backrooms of the Vatican by orthodox lobbyists, can have a substantial political impact. Apparently Benedict failed to recognize the explosive nature of this baptism. It marked the second time that he was responsible for serious consternation in the Islamic world.

The first was his 2006 speech in Regensburg that angered Muslims from Jakarta to Casablanca. In September 2006, Pope Benedict XVI, without so much as consulting with the relevant bodies in the Curia, delivered a lecture on faith and reason, and in doing so he unwittingly set off a global religious controversy. "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman," the pope said, quoting a Byzantine emperor. The speech quickly ignited outrage around the world. Islamic fundamentalists in Indonesia called for the pope's death, and in Somalia a nun who had worked in a children's clinic was shot. A pope had openly insinuated that another world religion showed a tendency toward violence, and a pope had cited a sentence critical of Islam without distancing himself from it clearly enough.

Ratzinger, who holds a doctorate in theology, wrote the speech himself, which shows that the Holy Father apparently has difficulty comprehending the public impact of his actions. Benedict has almost no sensitivity for the public mood, and he is no politician. His actions are based on other maxims, derived from theological tenets, dogmatic insights and the constraints of church law.

Wolfgang Thierse, a Catholic German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), thinks Benedict's gaffes come from his isolation. "The pope's faux pas and blunders show that he makes decisions on his own. In theological terms, he lives in a separate world, the world of the old church fathers who shaped him. This is why he barely notices the historical and political context. He claims to serve the truth, which is not incorrect. But he must combine it with a respect for other truths."

It is a weakness in his biography that Ratzinger has almost never left the confines of a strictly clerical environment. His contact with the world and other people was consistently kept to a minimum. His world is that which exits inside the church, including its old traditions. In that world all that counts is what can be read in books. Now, at his advanced age, he is anxious to prevent this world from fracturing.

"His current life," says a German theologian, "is reminiscent of Louis XVI. He hears snippets of what is happening in the world, signs something here and there, performs his duties, studies documents and has generally made a comfortable life for himself at court. But he is not the master of the machine that surrounds him."

The Bavarian pope's lack of worldliness is at times oddly amusing and at times horrifying. He wants to be a doctor of the church, most of all, ceaselessly presenting the truths of the faith. But he has little interest in how his church is positioned in this world. The theological pope blossoms when he can work his way through the apostles, bit by bit, during his Wednesday audiences, even discussing such unknown church fathers as St. Andrew of Crete.

Perhaps this explains the covert sympathy Benedict has for all the ultra-purists, the brothers of St. Pius and other Don Quixotes of a supposedly pure Catholicism. He resembles them in his deep pessimism about the course of the world, in his almost entomological passion for minute deviations from doctrine, and in his belief that the world is essentially made up of dogmas.

In his autobiographical "Milestones," Joseph Ratzinger criticized the Second Vatican Council. The hard break with traditions like the Tridentine mass, the old-style Roman Rite Mass, was a mistake, he writes. "I am convinced that the church crisis we are experiencing today is largely a result of the degeneration of the liturgy."

Every brother of St. Pius will agree with this, and with the programmatic address Ratzinger gave in April 2005, just before the conclave: "Having a clear faith, based on the Creed of the Church, is often labeled today as a fundamentalism. Whereas, relativism, which is letting oneself be tossed and swept along by every wind of teaching, looks like the only attitude (acceptable) to today's standards. We are moving towards a dictatorship of relativism which does not recognize anything as for certain and which has as its highest goal one's own ego and one's own desires."

Perhaps the See of Rome is in fact the only job in which such beliefs can still be reconciled with the job profile. If this is the case, however, there are bound to be regular collisions with the real world that exists outside the Leonine Wall surrounding the Vatican. The global, media-dominated society hears everything, sees everything, knows everything and forgets nothing. The Regensburg address made this clear, as does the current Williamson affair. And no amount of prayer can change this.

The Vatican must have known what kinds of thoughts the Lefebvre disciples harbored. Bishop Williamson's followers in Sweden posted a presentation on YouTube in which Williamson enthusiastically praises the so-called Syllabus as a litmus test for true Catholicism. For non-Catholics, the "Syllabus Errorum" is a list of the supposed fundamental errors of the modern age. These include concepts like democracy, the rule of law, freedom of religion, the separate of church and state, human rights, liberalism and rationalism. (Gay marriage is not mentioned explicitly, at least not yet.)

Pope Benedict gets involved with backward-looking pious types, because he sees himself as a servant of unity, as he explained last Wednesday. His step, he said, should be understood as an "act of paternal mercy, because these prelates had repeatedly manifested to me their deep pain at the situation in which they had come." He wanted to overcome a schism within the church, he said.

The SSPX consists of just 500 priests worldwide. In Germany it has chapels and churches in more than 50 locations and about 10,000 members. There are no precise numbers of worldwide membership, although it is estimated at between 100,000 and 200,000, distributed across 30 countries around the world. No more than 0.02 percent of all Catholics are members.

And yet Benedict seems willing to risk the reputation of his church for this small group. A fundamental theologian like Joseph Ratzinger can apparently put up with many things, just not secondary truths. "The pope has placed the welfare of the church above respect for the truth and the memory of the dead," says Vito Mancuso, a professor of Catholic theology in Milan, Italy.

In fact, there is evidence of a certain imbalance. The pope routinely blunders when it comes to the more liberal side of things, but never on the conservative side. This is borne out by many examples. For instance, at the opening ceremony for the Latin American Conference of Bishops in Aparecida, Brazil, in May 2007, the Bavarian pope snubbed all indigenous peoples when he said that their ancestors' conversion to Christianity did not constitute forcing the religion on a foreign culture, but instead was something the indigenous peoples had unconsciously desired.

"To say that the cultural decimation of our people constitutes a

purification is offensive and, to be honest, frightening," indigenous

representative Sandro Tuxá said at the time.

Benedict even manages to offend Protestants in his native Germany when he discusses the legitimate teachings of his church. In July 2007, Benedict authorized a document issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which stated that Protestants did not form "churches in the real sense." This was nothing new, from a Catholic perspective. For Rome there is only one church, namely its own, the "Una Sancta Catholica Ecclesia," which goes back to the Apostles. Everything else, in the Vatican's view, is nothing but sects, Christian communities or lay events.

In this respect, the pope is right. But was he well advised to point it out once again? At any rate, he has inflicted damage on the relationship among the denominations. "Some hoped that a pope who comes from Germany, and as such is quite familiar with the Protestant Church, would improve relations. These hopes have not been fulfilled," says Bishop Margot Kässmann from the northern German city of Hannover. In fact, official relations between Protestants and Catholics are relatively frosty at the moment.

Last November, Benedict XVI wrote the foreword for a book by Marcello Pero, a philosopher and former president of the Italian Senate. In it, the pope praises the rejection of a "cosmopolitan" Europe. "You explain with great clarity," Benedict writes, "that an interreligious dialogue, in the narrow sense of the word, is not possible, whereas the intercultural dialogue in which the cultural consequences of the fundamental religious decision are examined becomes all the more urgent." There can be no "true dialogue" about religion, Benedict continues, "without excluding one's own faith."

What some critics of the pope dismiss as naiveté and awkwardness in dealing with the world is far more for others. For them, the series of mishaps eventually turns into a pattern of stubbornness.

The papal gaffes strike a particularly sensitive note in those who have experienced too many supposed exceptions and blunder in their history, and have done so for so long that they were almost wiped out: the Jews.

The extension of the pope's hand in blessing to the most right-wing fringe of Christianity, an act of mercy for someone like Williamson, is "no regrettable isolated incident," says Walter Homolka, rector of the Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam outside Berlin. Instead, the rabbi sees it as "a cascade of incidents," which can only lead to the conclusion that "the Jewish-Christian relationship is of no value to the pope."

This statement is evidence of a deep bitterness. Joseph Ratzinger is anything but an anti-Semite. The common origins of Judaism and Christianity are at the core of his theological thought. In his "Introduction to Christianity," he approvingly cites a sentence by the "great Jewish theologian Leo Baeck," according to which all devout people, not just the Israelites, will share "in eternal bliss."

However, one can accuse the pope of assigning greater importance to inner unity of his church than to its relationship with other religions. This became clear, once again, to Jewish religious scholars when Benedict issued a so-called motu proprio document on the liturgy on July 7, 2007.

Since 1570, Catholics had prayed on Good Friday for the conversion of the "faithless Jews," and that "they may be delivered from their darkness." Catholics did this for 400 years, but their prayers never met with much success. The rite was modified after the Second Vatican Council, and the new version of the intercession read, somewhat more politely: " Let us pray for the Jewish people, the first to hear the Word of God, that they may continue to grow in the love of his name and in faithfulness to his covenant that they may reach the destination set by God's providence."

To the delight of traditionalists, Benedict's decree reinstated the Tridentine Mass in a special form. That form included all of the passages that were laid down in 1962, in the Roman Missal ("Missale Romanum"). But did it include the intercession for the Jews?

It sounds festive enough in Latin, but only because no one understands it. But the statement becomes more than clear in translation: "Let us pray for the Jews. May the Lord our God enlighten their hearts so that they may acknowledge Jesus Christ, the savior of all men. Almighty and everlasting God, you who want all men to be saved and to reach the awareness of the truth, graciously grant that, with the fullness of peoples entering into your church, all Israel may be saved. Through Christ our Lord. Amen."

For historian Michael Wolffsohn, the motu proprio was the

"biggest theological step backward in relation to Judaism since 1945."

The Jewish representatives in the Jewish and Christian working group

within the Central Committee of German Catholics then boycotted the

Catholic Assembly.

Benedict XVI's support for the process of beatification of Pope Pius XII is also a serious problem for history-conscious Jews in Israel and in the Diaspora. The Italian pope, for reasons of diplomatic caution or out of sheer fear, remained publicly silent on the Holocaust.

In September, Pope Benedict expressed his clear support for his "esteemed predecessor." At a conference of the Jewish-Christian Pave the Way Foundation, the pope spoke of Pius's "many interventions, made secretly and silently, precisely because, given the concrete situation of that difficult historical moment, only in this way was it possible to avoid the worst and save the greatest number of Jews." The achievements of the Pacelli pope were not always "examined in the right light."

Although Pius XII secretly saved the lives of many Jews, his name is still mentioned at Israel's Yad Washem Holocaust Memorial as an example of the failure of the church.

Former Italian President Francesco Cossiga is not surprised by the constantly recurring tensions. "We must not forget," he says, "that a strong anti-Jewish feeling is rooted in Catholicism. And two popes — Wojtyla and Ratzinger — are certainly not enough to put an end to this."

Even the Apostle Paul wrote about the Jews "who killed the Lord Jesus and the prophets, who have persecuted us, and who please neither God nor any group of people." For Christians, the Jews were the supposed "murderers of God" for almost two thousand years. Anti-Judaism permeates the history of the church — and it has often been bloody.

In the late 11th century, after Pope Urban II urged Christians to conquer the Holy Land, thousands of crusaders in France and Germany followed his call. But instead of traveling to Jerusalem, they first descended upon their Jewish neighbors at home. On a single day, Christian mobs, chanting "Let us avenge the blood of the Christ Crucified," murdered the entire Jewish community of about 1,000 people in the western city of Mainz.

Pogroms became commonplace. In 1298, bands of "Jew killers" led by a knight named Rindfleisch aus Röttingen traveled through the Franconia region and murdered about 5,000 Jews. Life was especially dangerous for Jews on Good Friday, when Christians, seized by their pious bloodlust, pursued the "god killers." By the end of the 15th century, Christians, through murder and forced displacement, had managed to wipe out the majority of Jewish populations in Western and Southern Europe.

Even Martin Luther, the reformer, was no friend of the Jews. He recommended: "First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them. Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed."

During the course of the 19th century, anti-Judaism was replaced and displaced by anti-Semitism, which was rooted in racism. According to theologian Hans Küng, "National Socialism would have been impossible without the centuries-old anti-Semitism of the churches." During Nazi rule, conflicts quickly arose between Catholic doctrine and the all-encompassing claim to power of party members. Although some bishops were headed for a clear course of confrontation with the Nazis, the annihilation of the Jews was by no means the German episcopate's greatest concern.

It was only in 1965 that Pope Paul VI, in the "Nostra aetate" declaration of the Second Vatican Council, rejected anti-Judaism once and for all. The church, the groundbreaking document read, "decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone."

It is precisely this document that Lefebvre's followers have not recognized to this day. The SSPX saw the Council essentially as a "fissure in the church," through which the "smoke of Satan had entered the Church."

The ultra-conservative group's representative in Germany is Father Franz Schmidberger, the District Superior of the SSPX in Stuttgart. After some hesitation, Schmidberger distanced himself from the statements of his fellow SSPX member Williamson. "The downplaying of the murders of Jews by the Nazi regime, and its atrocities, are unacceptable to us. I wish to apologize for this behavior and distance myself from all statements of this nature."

But shortly before Christmas, Schmidberger and his fellow SSPX members wrote to German bishops to remind them of the supposed Jewish original sin: "With the crucifixion of Christ, the curtain of the temple was torn and the old alliance destroyed. But this does not just mean that the Jews of today are not our older brothers in faith. Rather, they are complicit in deicide, as long as they do not distance themselves from the culpability of their forefathers by acknowledging the divinity of Christ and the baptism."

This age-old atavistic way of thinking, which defines Jews as being spattered with guilt, has been part of the church once again since Benedict's decree. This, in fact, is what happened on Jan. 24, 2009, and it cannot be reversed with any declarations or visits to synagogues.

Dieter Graumann, the vice-president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, calls it a "fiasco, an absolute disaster." A German, of all people, says Graumann, set the Christian-Jewish dialogue back by decades. "That's what makes it so bitter," says Graumann, "so sad, and so incomprehensible."

Oded Wiener, who, as Director General of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, is responsible for interfaith dialogue, says that there have been dramatic telephone conversations between Jerusalem and Rome, as part of an effort to salvage what can be salvaged. But there is a sense of deep disappointment. Elia Enrico Richetti, Venice's chief rabbi, initially terminated cooperation with the Catholic Church, because the pope lacked "the most basic respect" for the Jews. Richetti sees the pope's actions as the "obliteration of 50 years of church history."

Dialogue with the Jews was a central concern for Benedict's predecessor, John Paul II. He had experienced the murdering of Jews as a young man in Poland, and as pope he condemned anti-Semitism as a "sin against God and man." For John Paul, the Jews were "our older brothers."

Before Joseph Ratzinger was elected pope, Rabbi Walter Homolka spoke with him about the Christian-Jewish dialogue. "He was in favor of it," Homolka recalls, "but he didn't seem to feel very passionate about it." Homolka, who is in charge of training rabbis in Germany, no longer believes in an easing of tensions between Jews and the Catholic Church, as long as Benedict XVI is its leader. "We are waiting for the next pope," he says.

How the Jews will cope with this serious affront by the Vatican depends not only on the leadership in Rome, but also on the faithful around the world. Central Jewish Council Vice-president Graumann wants to see "Catholics stand up and show that they will not let down the Jews."

What next?

Jerusalem resident David Rosen is the chairman of the International Jewish Committee for Inter-religious Consultations. He was in the audience when Benedict gave a moving speech at the Auschwitz memorial, in which he said: "In a place like this, words fail; in the end, there can only be a dread silence — a silence which is itself a heartfelt cry to God: Why, Lord, did you remain silent? How could you tolerate all this? In silence, then, we bow our heads before the endless line of those who suffered and were put to death here... It is a duty before the truth and the just due of all who suffered here, a duty before God, for me to come here as the successor of Pope John Paul II and as a son of the German people."

The newly clear, though appallingly after-the-fact condemnation of anti-Semitism by Pope Benedict XVI gives Rosen hope that permanent damage has not been inflicted on the process of reconciliation between Jews and Christians.

Nevertheless, Rabbi Rosen has canceled an annual meeting with representatives of the Vatican scheduled for early March. "The church must now determine," says the influential rabbi, "whether the brothers of St. Pius share the teachings on anti-Semitism," such as John Paul II's characterization of anti-Semitism as "a sin against God and man."

Experts on Catholic Church law also believe that the schism will only end completely if the traditionalists clearly recognize the authority of the pope and the resolutions of the Second Vatican Council. If not, says Peter Krämer, an expert on canon law from the western German city of Trier, "the suspension from office would remain in effect." This is the conclusion he draws from Benedict's remarks on Wednesday.

"I hope," the pope said, "my gesture is followed by the hoped-for commitment on their part to take the further steps necessary to realize full communion with the church, thus witnessing true fidelity, and true recognition of the magisterium and the authority of the pope and of the Second Vatican Council."

There is at least one person who has so far shown no intention of recognizing anything at all.

Bishop Williamson is sitting in his Seminary of Our Lady Co-Redemptrix in La Reja, a confident neo-Baroque building 50 kilometers (31 miles) west of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Journalists are turned away. They are told that this is a vacation period and that the bishop does not wish to see anyone. But on the weekend, he referred to his comments on the Holocaust as "imprudent" and said that he regretted having caused "unnecessary concerns" for Benedict. But there was little remorse in his words.

Shortly before officials at the SSPX headquarters in Switzerland ordered Williamson not to speak to the press, he wrote a letter to his loyal supporters. Its tone was triumphant: "In my opinion this latter Decree is a great step forward for the Church without being a betrayal on the part of the SSPX ... And let us thank and pray for Benedict XVI and all his collaborators who helped to push through this Decree, despite, for instance, a media uproar orchestrated and timed to prevent it."

His words are clear. And the traditionalists are right in one respect: They have reason to celebrate. They have successfully completed another step back into the Unam et Sanctam, and have done so without making any concessions whatsoever.

Joseph Ratzinger, the learned theology professor, apparently never wanted this office. The Holy Spirit elevated him to the Holy See, he said after the conclave, referring to himself as "a simple and humble worker in the Lord's vineyard."

But his work in the vineyard has since turned into the way of the cross.

Despite all efforts to engage in dialogue with China, the churches of the East, and Islam, this pope has repeatedly stumbled on the issue of the Holocaust, as if he were condemned to do so. The affair over the rehabilitation of the traditionalists is another station of the cross for Benedict.

Benedict XVI will likely be the last pope to have consciously

experienced the nightmare of the Nazi era. Perhaps it is no accident,

but an irony of history, that Joseph Ratzinger, a former member of the

Hitler Youth from the Bavarian town of Marktl am Inn, must repeatedly

shoulder the burden of this history — whether he wants to or not.

RELATED SPIEGEL ONLINE LINKS

CHRONICLING THE CHURCH'S BLUNDERS

November 2008

During an interview in Germany with a Swedish TV station, Bishop Richard Williamson denies that Jews were gassed during the Third Reich. "I believe there were no gas chambers," he says. He also says that only 200,000 to 300,000 Jews died in German concentration camps instead of the commonly accepted number of 6 million.

January 19, 2009

DER SPIEGEL reports on Williamson's TV interview.

January 21

The interview is aired on Jan. 21, two days after the SPIEGEL report. That same day, Pope Benedict XVI signs a decree lifting the excommunication of four bishops associated with the ultra-conservative Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX). Holocaust denier Williamson is one of those pardoned.

January 22

On Thursday, the Italian daily Il Giornale reports on the decree.

January 23

On Friday, the Catholic news agency KNA reports that the public prosecutor's office in the German city of Regensburg is suing Bishop Williamson for breaking German law regarding Holocaust denial. That same day, the report is aired on Vatican Radio and posted on its Web site.

January 24

On Saturday, the pope officially announces that he plans to accept four bishops from SSPX back into the Catholic Church. Vatican spokesperson Federico Lombardi celebrates the decision as "an important step toward a complete unification" of the Catholic Church.

January 26

The debate heats up. Vice President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany Dieter Graumann calls Benedict's decision an "incomprehensible act of provocation." Germany's Conference of Bishops distances itself from Williamson. Vice President of Germany's Central Committee of Catholics Heinz-Wilhelm Brockmann defends the pope's actions as "an attempt to unify the Church."

January 28

During his Wednesday audience at the Vatican, Pope Benedict XVI denounces Holocaust denial. He offers reassurance to Jews that they have his "full and indisputable solidarity."

January 29

Vatican spokesperson Federico Lombardi explains that whoever denies the Holocaust is "denying Christian beliefs." He adds: "And that is an even more serious error when committed priests and bishops."

January 29

Cardinal Dario Castrillon Hoyos claims to have known nothing of Williamson's controversial TV interview when the decree was released. Hoyos was the one to lead discussions with SSPX on lifting the excommunication. The Central Council of Jews in Germany breaks off dialogue with the Catholic Church.

January 30

The pope promotes the ultraconservative priest Gerhard Wagner to become an auxiliary bishop in Linz. Bishop Richard Williamson apologizes to the pope for causing "inconveniences and problems."

January 31

In an interview with SPIEGEL, Israeli Minister for Religious Affairs Yitzhak Cohen threatens that Israel may break off diplomatic relations with the Vatican.

February 1

Renowned Belgian professor of theology and ethics Jean-Pierre Wils publicly announces that he had left the Catholic Church.

February 2

SPXX demands more power in the Vatican. Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais tells Italy's newspaper, La Stampa that he and his followers will not be satisfied with simply being brought back into the Church: "We will not change our position but will rather change Rome."

February 3

Chancellor Angela Merkel demands that the pope clarify his position and tell the SSPX with no uncertainty that Holocaust denial cannot be accepted. "I do not believe that sufficient clarification has been made," she says.

February 4

The Vatican demands that Williamson, "in an absolutely unequivocal and public fashion," distance himself from Holocaust denial before he can be fully readmitted to the Catholic Church. The Vatican also admits that it was unaware of Williamson's view when it decided to revoke his excommunication.

February 5

Chancellor Merkel welcomes the pope's demand for Williamson to recant his Holocaust denial. Other German politicians remain critical and say more needs to be done.

This article was published February 4, 2009 in Der Spiegel Thanks are due to Shoshanna Walker for sending in this article.

How Could This Have Happened?

Sloppy Work

PART 3: ISOLATED WITHIN THE CONFINES OF DOCTRINE

Critical of Islam

'Degeneration of the Liturgy'

Evidence of a Certain Misbalance

PART 4: KILLING JEWS — PRAYING FOR JEWS

Praying for the Jews

Step Backward

Pogroms Became Commonplace

'Smoke of Satan'

PART 5: BENEDICT BEARING THE CROSS

'Obliteration of 50 Years of Church History'

No Permanent Damage?

Working in the Lord's Vineyard

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,605542,00.html

It was translated from the German by Christopher Sultan.

HOME

January-February 2009 Featured Stories

Background Information

News On The Web