WAS BRITAIN'S SEVERING TRANSJORDAN FROM THE JEWISH HOMELAND AN ACT OF PREJUDICE, MISJUDGMENT OR BETRAYAL OF THE JEWS?

by Alex Rose

"I would remind you (excuse me for quoting an example known to everyone of you) of the commotion which was produced in that famous institution when Oliver Twist came and asked for "more". He said "more" because he did not how to express it; what Oliver Twist really meant was this : "Will you just give me that normal portion which is necessary for a boy of my age to be able to live?" — Vladimir (Zev) Jabotinsky during a presentation to the Peel Commission, February 11, 1937)

This paper addresses pertinent international law and divergent political interpretations of the law as applied to the nascent state of Israel. It will also show how the origins of the Arab-Jewish dispute and British involvement impact events even today. We will attempt to distinguish actual international law from non-binding UN resolutions and the war of ideas.

Because of the pertinence of Articles 5, 15 and 25 to the discussion, we reproduce them here in full:

ARTICLE 5. The Mandatory shall be responsible for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of the Government of any foreign Power.

ARTICLE 15. The Mandatory shall see that complete freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship, subject only to the maintenance of public order and morals, are ensured to all. No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief.

ARTICLE 25. In the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those conditions, provided that no action shall be taken which is inconsistent with the provisions of Articles 15, 16 and 18.

A Brief History Of Deceit And Reneging On Promises

From the second half of the 19th century, when significant numbers of Jews began coming home determined to reclaim and redeem the Jewish homeland, Zionism was beset by power politics, with much of the negativity coming from Britain, which had pledged itself to help birth a state for the Jews. Gersion Appel in his 1942 paper, Zionism And Power Politics,[1] describes it this way:

In laying out his disturbing story of Britain misusing its trusteeship of the eventual Jewish state and how the Zionists would have to be alert for opportunities made possible by unfolding events, Appel weaves in observations made by famed world traveler and journalist, Pierre van Paassen,[2]. Appel writes:The history of British Mandate rule in Palestine since the Balfour Declaration manifests an unbroken chain of restrictions on Zionist growth beginning with the very day Britain placed the administration of Palestine in the hands of the Colonial Office, rather than the Foreign Office as France had done in Syria. This immediately signified her intention to make Palestine subservient to imperialist interests. The next step in this direction was the Churchill White Paper of 1921 severing Trans Jordan from Palestine and prohibiting Jewish settlement there, thereby succeeding in making it Judenrein. This was followed by its criminal part in the riots of the 20's and the 30's, the Partition Plan, and the present White Paper with its restrictions on Jewish immigration and land sale to Jews, virtually stifling Zionist growth in Palestine. The White Paper is still the official British policy as regards Palestine, and moreover there is every indication that it is being rigidly enforced and will continue to be so enforced despite the changed world conditions brought on by the war.

Viewed in the light of history and the interactions of events and affairs within the past two decades of British Mandate rule, it will be clearly seen that the British Mandate power was following neither a whimsical nor muddling course in Palestine but a deliberate, ruthless, and consistent anti-Zionist policy. Zionism ended its usefulness to Britain with the granting of the Mandate.

As Pierre Van Paassen incisively points out in "Days of Our Years", it is British policy to have Palestine as a part of the British system of imperial defense: an important link in the overland route to her Indian empire and a strategic military bastion in the near east, with Haifa as the terminus to the pipe line from the Mosul oil fields, and filling stations for her military machine. The Jewish National Home sprawled all over it and peopled with Jews who are notoriously for peace and against war is not to her liking. It would serve her purpose best to deal with a few Arab feudal lords whom she can easily bribe into submission and a handful of ignorant Arab peasants who can be used cheaply for labor on the construction of the strategic military points in Palestine. Therefore, in pursuit of this policy, the Colonial Office has constantly fostered Pan Arabism as the surest safeguard to the empire by using Palestine as the lever in the process. Insidiously maintaining in Palestine a policy of divide and rule, they tried to create an Arab nationalism that never existed and cement it by making possession of Palestine the 'cause célèbre' of the Arab peoples.

Nevertheless, whether we or the British like it or not, conditions are changing. New political scents are in the wind, new power alignments are taking form the world over, and particularly in the Near and Far East. All of these phenomena are symptomatic of a revolutionary undercurrent that foreshadows a completely changed picture politically and economically in the Near East after the war. Zionism, as any other political movement, lives and thrives on political opportunities created by the changing fortune of world events. If it is to play a game of power politics, where the stakes are high and the cards are stacked, - and we have no choice but to play - there must be no amateurish, sentimentally naïve bungling of opportunities. We must read the signs of the times and calculate political moves with scientific precision.

We, of the present generation, are witnessing a world revolution in its most decisive step; a new world order is taking shape before our eyes, and Zionism with all its aspirations will have to find its place in that world pattern that is unfolding. The era of untrammeled economic and political imperialism is fast drawing to a close. The imperialist structure that the British Empire built is crumbling from the sheer weight of its own iniquities and the relentless, crushing power of liberal thought. In Asia, the enslaved masses are acquiring a powerful pivotal position as a result of the exigencies of the war, and they are daily becoming more articulate and coherent in their demands for a rightful share in the world's freedom. The unknowns and incalculables of today, India and China, with a potential power of millions, will be important decisive factors of tomorrow. We dare not ignore these developments.

Political and economic trends point to a limitation of the British imperialist spheres after the war. To continue to chain our Zionist hopes to the chariot of British imperialism is a policy fraught with danger for any peaceful, enduring society in Palestine. It is therefore imperative that we begin to think in terms of a new orientation in our relationship with the British Mandate Power. World events and portents of the future, as well as the lesson of two decades of ceaseless, consistent, and unadulterated British anti-Zionist policy leaves us no other choice. We dare not blind ourselves to the realities of power politics, and we have not the moral right to jeopardize an ideal that has been giving life and hope to countless Jews for centuries.

During a visit to Palestine in 1926, van Paassen remarked that the transformation of Palestine is one of the wonders of our age. His admiration for the early Jewish settlers toiling against all odds fills many pages. To him, their restoration of the area which for centuries had been plundered by many nationalities following the state of the Jews in antiquity was miraculous. In his travels throughout Palestine, Pierre van Paassen interviewed many historical characters including the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammad Amin al-Husayn, the British Acting High Commissioner, H.C. Luke and Sir Herbert Samuel. His description of the various Arab riots are exacting and complete in every respect. Following an inspection of the inhuman destruction in Hebron in 1929 at the hands of the Mufti's gangs, he heard the British governor of the Jaffa district callously remarking" Shall we have lunch now or drive to Jerusalem first?"

During his interview, the Mufti expressed these thoughts:

[a] "There will be no peace in this country until they go. In the English, we recognize our real enemies. It is the British government and not the Jews who have foisted the scandalous Balfour Declaration on us."

[b] The disturbances would not terminate till both till both the Jews and the English had evacuated Palestine.

[c] He maintained that " my country" was being ruined by Jews. Further, he accused the Jews of "stealing our land. They want everything we have." He also spoke about instituting economic boycotts against the Jews.

Van Paassen's response was personal and accusatory. He pointed to the bloodshed and violence during the recent riots as showing intention to paralyze the process of building a Jewish National Home. The riots he said "were an attempt to strike terror in the hearts of the Zionists." As for who was responsible "for what your Eminence calls 'these horrible outbreaks', public opinion in France and in America, I am sorry to say, points directly to yourself." The much-angered Mufti attempted to defend himself refuting the accusations by resorting to outright lies.

Pierre van Paassen's interface with Harry C Luke, Assistant Governor of Jerusalem wasn't any less to the point. Luke's claimed he was fair to both the Arabs and Jews, because "We are charged with unfairness by both Jews and Arabs, something that is of course the best proof of our impartiality." To this, van Paassen, reminded him that it was the Jews who'd tried to defend themselves that were arrested, not the Arabs. In noting that Britain was charged by the League of Nations to make it possible for the Jews to build their National home, van Passen understood it was the Arabs who objected and engaged in violence. "But what is harder to understand is that these Arabs believe the government to be on their side, for that was the general battle cry of the rioters in the recent attacks." After an extensive exchange of arguments, van Paassen terminated the discussions with a penetrating remark, "It does not look to me, sir that this is fundamentally a quarrel between Jews and Arabs." [2]

It Is Often Said That Nations Have Interests. What Is Not Accounted For In This Is The Matter Of Ethics

Shmuel Katz, a member of Israel's first Knesset, an Irgun leader and renowned author/journalist, in his books "Lone Wolf" and "Battleground" provides an extensive background to the British dissection of Transjordan from the Palestine Mandate.

From "Battleground",

'It is impossible and, indeed, pointless and misleading to explain, analyze, or trace the development of Arab hostility to Zionism and the origins of Arab claims in Palestine without examining the policy of the British rulers of the country between 1919 and 1948.

One of the great objects of British diplomacy as the conflict in Palestine deepened during the Mandate period was to create the image of Britain as an honest arbiter striving only for the best for all concerned and for justice. In fact, Britain was an active participant in the confrontation. She was indeed more than a party.

Shmuel Katz explains how "the release in recent years of even a part of the confidential official documents of the time has strengthened the long-held suspicion that the Arab attack on Zionism would never have began had it not been for British inspiration, tutelage and guidance." Katz writes:

In the end, it is true, British sympathy, assistance, and cooperation came to be auxiliary to Arab attitudes and actions. Those attitudes, however, had their beginnings and their original motive power as a function of British imperial ambitions and policy.

[...]

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, providing for an international

administration in Palestine, was the original reason for the exclusion of Palestine from the promises made to Hussein. But in 1917, the British government published the Balfour Declaration for the establishment of the Jewish National Home in Palestine. To achieve this promise of support in the restoration of their ancient homeland, issued after much negotiation and deep consideration, the Jews made a significant contribution to the British war effort. Whatever fantastic interpretations were later put on it, the British intention was clear and was understood clearly at the time. A Jewish state was to be established — not at once, but as soon as the Jewish People by immigration and development become a majority in the still largely derelict and nearly empty country with its then half-million Arabs and 90,000 Jews.[...]

France, pressing her claim to Syria and Lebanon, was granted control over them by the Peace Conference. In defiance of this decision, a so-called General Syrian Congress offered the throne of Syria to Faisal; he was subsequently installed in Damascus, where he set up an administration. The Supreme Allied Council in Paris retorted by formally granting the Mandate over Syria. and Lebanon to France. This duality could not last. In July 1920, the French ordered Faisal out of the country.

Faisal, bereft of the Syrian crown for which Lawrence and the Arab Bureau had labored so hard, was instead offered the throne of Iraq by the. British, though it had previously been earmarked for Faisal's younger brother Abdullah ibn-Hussein, who was thus left without a throne.

The British feared, or were induced to fear, that the French, angered by Abdullah's threats, would invade eastern Palestine. They therefore casually suggested to Abdullah that he forget about Syria and instead become a representative of Britain in administering eastern Palestine on behalf of the Mandatory authority. Whereupon Abdullah generously assigned himself to the French presence in Syria and took up office in Transjordan, and in time accepted it as a substitute.

The British government then recalled that eastern Palestine was part of the area pledged to the Jewish people. They thereupon inserted an alteration in the draft text of the Mandate (then not yet ratified by the League of Nations), which gave Britain the right to "postpone or withhold" the provisions of the Mandate relating to the Jewish National Home "in the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined." The Zionist leaders were stunned by this threatened lopping off of three quarters of the area of the projected Jewish National Home; its establishment had, after all, been Britain's warrant for being granted the Mandate. But the British government countered with the proposal that, if the Zionists did not accept the situation, Britain would decline the Mandate altogether and thus withdraw her protection from the Jewish restoration.

Thus, as a purely British manufacture, filched from the Jewish National Home, torn out of Palestine of which it had always been an integral part, there was brought into being from the empty waste what subsequently became a spearhead in the "Arab" onslaught on the Jewish state, the Emirate of Transjordan, later expanded across the river and renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

The elimination of eastern Palestine in 1921-1923 was only the first act —though stark, dramatic, and momentous — in a developing effort by the British to frustrate and emasculate the Jewish restoration that began in Palestine immediately after the British occupation.

The mechanism applied is entitled Article 25 of the Mandate. Now, was this not in direct conflict with Article 5, which reads, 'The Mandatory shall be responsible for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of, the Government of any foreign Power'? At the time, Palestine was ruled by the British Military Administration in Jerusalem who made no secret of its hostility to Zionism. For more than two years, it neither published nor allowed the publication of the Balfour Declaration In Palestine. The Declaration, wrote the Chief Political Officer in Cairo to the Chief Administrator in Jerusalem on October 9, 1919, 'is to be treated as extremely confidential and is on no account for any publication.' [3] P45, 54, 56, 59, 61.

Legal Rights and Title of Sovereignty of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel and Palestine under International Law

There has been no more prolific writer on the subject of the Legal Rights and Title of Sovereignty of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel and Palestine under International Law than Howard Grief, a Canadian attorney, renowned author, and an Israeli citizen. What follows is taken directly from his monumental paper published in NATIV during 2004 with an introduction to his book in ACR 2003. [Policy Paper # 147, 2003]

Grief explains that these rights were recognized as inherent in the Jewish people when the highest representatives of the Great Powers who had defeated Germany and Turkey in WW1 met at the Paris and San Remo Peace Conferences in 1919/1920. Under the settlement, the whole of Palestine on both sides of the Jordan was reserved exclusively for the Jewish people as the Jewish National Home, in recognition of their historical connection with that country, dating from the Patriarchal Period. Its boundaries were to be delineated in accordance with the historical and biblical formula 'from Dan to Beersheba', which denoted the entire Land of Israel. The Arabs were accorded national rights in Syria, Mesopotamia and Arabia, but NOT in Palestine. The British Government as Mandatory, Trustee and Tutor was charged with the obligation to create an eventual independent Jewish state in Palestine, and for this purpose ONLY it could exercise the attributes of sovereignty vested in the Jewish people.

The Palestine aspect of the global settlement was recorded in three basic documents which led to the founding of the modern State of Israel: the San Remo Resolution of April 25, 1920, combining the Balfour Declaration with the general provisions of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, the Mandate for Palestine confirmed on July 24, 1922 and the Franco-British Boundary Convention of December 23, 1920, supplemented by the Anglo-American Convention of 3, 1924 respecting the Mandate for Palestine.

In the Introduction, Howard Grief summarizes the British repudiation of its solemn obligation to develop Palestine gradually into an independent state, commencing with the June 3, 1922 White Paper and culminating in the May 17, 1939 MacDonald White Paper. He points to the US collaboration by aiding and abetting the 'British betrayal' of the Jewish people by 'its abject failure to act decisively against the 1939 White Paper despite its own legal obligation to do so under the 1924 treaty.' Despite all the intriguing activities of the various parties, Grief informs us that Jewish rights to all of Palestine 'remain in full force by virtue of the Principle of Acquired Rights and the Doctrine of Estoppel that apply in all legal systems of the democratic world.'[4] P1,2.

On Facebook, a copy of a February 04, 2013 letter by Grief sent to Saloman Benzimra of Canada is recorded, resulting from adverse comments made by a certain Richard Witty concerning Israel's Rights Under International Law on a commentary by Eugene Kontorovitch, a law professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. This is a snapshot of the points made by Howard Grief:

[a] Shortly after Winston Churchill assumed office as Colonial Secretary on February 14, 1921, Abdullah, the Emir of the Hedjaz arrived in Amman on March 1921. With an irregular force of fighters, he threatened to attack the French position in Syria for expelling his younger brother, Emir Feisel from the country and to restore Hashemite rule. This threat was nothing more than a worthless bluff, but succeeded in inducing Churchill to convene the Cairo Conference in March 1921 to settle the question of Transjordan, which was no longer under Feisel's temporary rule since his expulsion from Syria and to also secure for him the Kingdom of Iraq.

[b] Transjordan was certain to be included in the Mandate for Palestine and to be part of the Jewish National Home as both Lloyd George and Lord Balfour insisted and as agreed to by Feisel himself. Churchill wanted to pacify the Hashemite family for its loss of Syria and did so at the expense of the Jewish National Home by removing Transjordan from its scope and applicability. He did this on the advice of T.E. Lawrence as well as that of Sir Herbert Samuel and other senior officials in the Colonial Office.

[c] Churchill managed to convince the Lloyd George government to approve his plan to separate Transjordan from the Jewish National Home as well as his appointment of Abdullah as the administrator of the territory for a limited period of 6 months. Legally, even after it was separated from the Jewish national Home, Transjordan still remained an integral part of the Mandate for Palestine subject to its provisions except those relating to the Jewish National Home. It must be emphasized that Transjordan's detachment from the Jewish National Home was only meant to be a provisional or temporary measure as clearly indicated by the words in Article 25 of the Mandate, that the Mandatory Power had decided 'to postpone or withhold application of such provisions' of the Mandate it considered inapplicable 'to the existing local conditions' in Transjordan. In the mind of Abdullah, however, the detachment was permanent, an outlook shared with him by the new British Government and all subsequent governments. He was assured of this on a trip to London in October, 1922, the assurance being conditional upon his independent government in being constitutional. Upon this assurance being officially broadcast in Amman on May 25, 1923, by the High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, Abdullah considered this assurance to be a legal recognition of Transjordan's independence and not merely that his government was independent, regardless of the restrictions that existed under the Mandate.

At this junction, we need to consider the impact of the addition of Article 25 in contrast to Article 5, where the Mandatory 'shall be responsible for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of the Government of any Foreign Power.' But for the fact that the 'separation' was made permanent on May 25, 1946 with the declaration of Jordan as a sovereign and independent kingdom, it would appear not to be an illegitimate act. We need also question the intent of Britain as pursuing national interests or prejudice towards the Arabs versus the Jews. The role of George Nathanial Curzon who replaced Lord Balfour as Foreign Secretary in October, 1919 was most certainly a factor in that he was known to be an avowed anti-Zionist.

Grief continues by stating that Churchill's actions in the year's 1921-1922 robbed the Jewish people of their legal right to Transjordan and created a bad precedent for the partition of Palestine. Churchill did a lot more harm to the Zionist cause by re-interpreting the meaning of the term 'Jewish National Home' as found in the Balfour Declaration. With the issuing of the British White Paper on June 3, 1922, he redefined it to only mean a cultural or spiritual centre 'in which the Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion or race, an interest and a pride.' This action was seen by Grief as hypocritical given Churchill previously, in 1920, informing the French negotiators on boundaries that Transjordan was needed 'for the economic development of the Jewish National Home' and consequently France could not obtain it. Against this action, there is a need to recall Churchill's article published in the British Sunday newspaper, The Illustrated Sunday Herald on February 8, 1920 to proclaiming that he foresaw the creation in his lifetime a Jewish State 'by the banks of the Jordan'.

On June 21, 1921, Richard Meinertzhagen, a military adviser in Churchill's Colonial office 'foaming at the mouth with anger and indignation' had a heated meeting with him. According to entries entered in Meinertzhagen's diary, he informed Churchill that '... it was grossly unfair to the Jews, that it was yet another promise broken and that it was a most dishonest act, that the Balfour Declaration was being torn up by degrees and that the official policy of His Majesty's Government to establish a Home for the Jews in Biblical Palestine was being sabotaged.' In his opinion, Abdullah's rule in Transjordan ought to be of a temporary nature. 'say for 7 years and a guarantee give that Abdullah should never be given sovereign power over what was in fact Jewish territory'. Churchill reacted, 'he saw the force of my argument and would consider the question'. However, he thought that it was too late to alter the situation, 'but a time limit to Abdullah's rule might work'. No time limit was placed on Abdullah's rule and what was to be only a temporary measure, lasted almost the entire period of the Mandate.

At this point, Grief informs us that, 'In my considered legal opinion, the State of Israel still has dormant legal rights to Transjordan, which however cannot be exercised, unless Jordan as a state disintegrates...' [5] P1-7.

On June 3, 1922, Britain published the Churchill White Paper [also known as the British White Paper of 1922], to clarify how Britain viewed the Balfour Declaration of 1917, their intention being to aid the 'establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. Encyclopedia.com presents a snapshot of the proceedings:

"Drafted by the first high commissioner of Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, the White paper (also called the Churchill memorandum) was issued in the name of Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill in June 1922. A year earlier the Palestinians participated in political violence against the Jews, which a British commission found to have been caused by Arab hostility "connected with Jewish immigration and with their conception of Zionist policy." Samuel therefore urged Churchill to clarify to both communities the meaning of the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 and to reassure the Palestinians.

The Churchill statement reaffirmed British commitment to the Jewish national home. It declared that the Jews were in Palestine "as a right and not on sufferance" and defined the Jewish national home as "the further development of the existing Jewish community [Yishuv], with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that it may become a centre in which the Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion and race [sic], an interest and a pride." In order to fulfill the Balfour policy, "it is necessary that the Jewish community in Palestine should be able to increase its numbers by immigration."

At the same time, the memorandum rejected Zionist statements "to the effect that the purpose in view is to create a wholly Jewish Palestine," which would become " 'as Jewish as England is English.' His Majesty's Government regard any such expectations as impracticable and have no such aim in view." It assured the indigenous Palestinians that the British never considered "the disappearance or the subordination of the Arabic [sic ] population, language, or culture in Palestine" or even "the imposition of Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a whole." In addition, the allowable number of Jewish immigrants would be limited to the "economic capacity of the country."

The Zionist leaders regarded the memorandum as a whittling down of the Balfour Declaration but acquiesced, partly because of a veiled threat from the British government and partly because, off the record, the Zionists knew that there was nothing in the paper to preclude a Jewish state. (Churchill himself testified to the Peel Commission in 1936 that no such prohibition had been intended in his 1922 memorandum.) The Palestinians rejected the paper because it reaffirmed the Balfour policy. They were convinced that continued Jewish immigration would lead to a Jewish majority that would eventually dominate or dispossess them. Both Zionist and Palestinian interpretations of the memorandum were largely valid: The British did pare down their support for the Zionist program, but the Balfour policy remained intact long enough to allow extensive Jewish immigration and the establishment of semiautonomous Jewish governmental and military institutions" [6]

Omitted was this information from The Avalon Project:

"In this connection it has been observed with satisfaction that at a meeting of the Zionist Congress, the supreme governing body of the Zionist Organization, held at Carlsbad in September, 1921, a resolution was passed expressing as the official statement of Zionist aims "the determination of the Jewish people to live with the Arab people on terms of unity and mutual respect, and together with them to make the common home into a flourishing community, the up building of which may assure to each of its peoples an undisturbed national development."[7]

Conclusions

Was Britain's actions a matter of betrayal or one of pragmatism? To determine the truth, contributions by two legal experts will undoubtedly assist. Eugene Kontorovich, a law professor at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, has established himself as an expert on international law. The center piece of his "The legal Case for Israel" [See video here] correctly depicts the borders of the Jewish National Home as embracing all of the Land of Israel west of the Jordan as well as that of present day Jordan. As confirmation of his assertions, Kontorovich stresses UN Resolutions are not international law.

Douglas J. Feith, an attorney in the Washington DC law firm of Feith and Zell, served during the Reagan administration as deputy assistant secretary of defense and as a Middle East specialist on the White House National Security Council staff. His "A Mandate for Israel" published in the Number 33 Fall 1993 edition of The National Interest has most certainly stood the test of time. This is a minuscule selection

"International law, of which the Mandate is a part, specifically validates Jewish claims in Palestine and recognizes those claims as arising from "the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine." Arab opponents of Zionism have, from the beginning, opposed this view."

"Even before Britain had decided to shrink the Jewish national home, Balfour, speaking of the entire Mandate territory on both sides of the Jordan, expressed the hope that the Arabs 'will not grudge that small notch...in what are now Arab territories given to the [Jewish] people who for all these hundreds of years have been separated from it.' Though nearly 80% of that 'small notch' was soon made off limits to the Jews, the Arab powers continued to 'grudge' a Jewish state in Palestine."

American policymakers show a powerful disinclination to enter into the kind of legal and historical issues raised here. They dismiss them as academic — disconnected from the practical realities of war and diplomacy. Yet these same policy makers attribute enormous value to negotiations and peace agreements. The inconsistency can be dangerous.

Despite the clear intent for the future state of Israel to be on both sides of the Jordan river, on the face of it, British action in cutting away the larger portion, the east side of the Jordan, from Palestine was not illegal in the sense that that is what was presented to the League of Nations and that is what became law. But the significance of the words 'to postpone or withhold' in Article 25 must also be considered. Taking them not only at face value but in the context of all the previous history of the intent of the Mandate, allowing the Arabs to administer Transjordan was a temporary measure until such time as a majority Jewish population could take charge. It did not encompass elevating the territory of Transjordan into the Arab State of Jordan. Putting it bluntly, what began as a pragmatic measure became an act of betrayal of Britain's commitment when it took upon itself the charge to help the Jews create the conditions that would recreate a viable and thriving Jewish state in their ancient homeland.

The authors of the Justice Now 4 Israel site have furnished another valid perspective on the arguments questioning the legality of British behavior in the transition from Transjordan to Jordan while ignoring Articles 5, 15, and 25. Quoting from the Justice Now 4 Israel website:

The wording, "postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he [His Britannic Majesty] may considered inapplicable to the existing local conditions is by the nature of the wording a temporary action. That action was only valid until there was a change in the conditions leading to that decision. It did not authorize the British to permanently cut off portions of the land and turn it over to a foreign people.Furthermore, according to Article 25, the postponement or withholding of the application of the Mandate in Trans-Jordan could not be inconsistent with Article 15 of the Mandate for Palestine which states:

"No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief."The British "White Papers" policies, which prohibited Jewish settlement East of the Jordan, while allowing a foreign group of Arabs (the Hashemites) to settle and eventually be given all of Trans-Jordan, was in clear violation of Article 15, as well as Article 5 of the Mandate which stated that "no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of the Government of any foreign power."

[1] Gersion Appel: "Zionism and Power Politics". Word

Press.com. 1942.

http://gersionappel.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/zionism-and-power-politics.pdf.

[2] Pierre van Paassen: Days of our Years - After 7 Centuries. PP364-365, PP367-369.

[3] Shmuel Katz: Battleground: Facts and Fantasy in Palestine. (Taylor Productions) P45, P54, P56;

[4] Howard Grief: Policy Paper #147, 2003. Ariel Center for Policy Research [ACPR]. PP1-2.

[5] Howard Grief: "Israel's Rights Under International Law," copy of letter sent to Salomon Benzimra of Canada on February 04, 2013. Facebook PP1-7.

[6] Churchill White Paper 1922:

www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-34246000677.html/Paper. 1922. Para. 1-4.

[7] British White Paper: avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/brwh1922.asp. June 1922. Para 3 Line 11.

- Martin Gilbert. "An Overwhelmingly Jewish State - from the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate"

- Connor Cruise O'Brien. The Siege

- Raphael Medoff. Zionism And The Arabs: An American Jewish Dilemma 1898-1948

- Sidney

Zion. "The Palestine Problem: It's All In A Name." July 31, 2003.

http://www.jewishpress.com/news_article_print.asp?article=2674" - Isaiah Friedman. The Question Of Palestine: British-Jewish-Arab Relations, 1914-1918

- Isaiah Friedman. British Pan-Arab Policy 1915-1922

- Isaiah Friedman. Palestine: A Twice-Promised Land?: the British, the Arabs and Zionism, 1915-1920

- Samuel Katz. Lone Wolf

- David Fromkin. A Peace To End All Peace

- Benjamin Netanyahu. A Place Among The Nations

- Lewis Lipkin. "The Loss of East Palestine: British Perfidy, Jewish Infirmity Of Purpose And Arab Intransigence"

- Meir Abelson. "Palestine: The Original Sin"

- Emmanuel Navon. Zionism And Truth: The Case For The Jewish State

Martin Gilbert. "An Overwhelmingly Jewish State - From The

Balfour Declaration To The Palestine Mandate." JCPA.

http://www.jcpa.org/text/israel-rights/kiyum-gilbert.pdf

This article by Martin Gilbert is an interesting backgrounder for the period from the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate. An expansion on the 1922 White Paper, it is printed in full because of its obvious importance. See Footnote [23] below. — AR

On 22 July 1922, when the League of Nations announced the terms of Britain's Mandate for Palestine, it gave prominence to the Balfour Declaration. 'The Mandatory should be responsible,' the preamble stated, 'for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty...in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people...'[1] The preamble of the Mandate included the precise wording of the Balfour Declaration. Nothing in the Balfour Declaration dealt with Jewish statehood, immigration, land purchase or the boundaries of Palestine. This essay examines how British policy with regard to the 'national home for the Jewish people' evolved between November 1917 and July 1922, and the stages by which the Mandate commitments were reached.

In the discussions on the eve of the Balfour Declaration, the British War Cabinet, desperate to persuade the Jews of Russia to urge their government to renew Russia's war effort, saw Palestine as a Jewish rallying cry. To this end, those advising the War Cabinet, and the Foreign Secretary himself, A.J. Balfour, encouraged at least the possibility of an eventual Jewish majority, even if it might — with the settled population of Palestine then being some 600,000 Arabs and 60,000 Jews — be many years before such a majority emerged. On 31 October 1917, Balfour had told the War Cabinet that while the words 'national home...did not necessarily involve the early establishment of an independent Jewish State', such a State 'was a matter for gradual development in accordance with the ordinary laws of political evolution'.[2]

How these laws were to be regarded was explained in a Foreign Office memorandum of 19 December 1917 by Arnold Toynbee and Lewis Namier, the latter a Galician-born Jew, who wrote jointly:

'The objection raised against the Jews being given exclusive political rights in Palestine on a basis that would be undemocratic with regard to the local Christian and Mohammedan population, 'they wrote, 'is certainly the most important which the anti-Zionists have hitherto raised, but the difficulty is imaginary. Palestine might be held in trust by Great Britain or America until there was a sufficient population in the country fit to govern it on European lines. Then no undemocratic restrictions of the kind indicated in the memorandum would be required any longer.'[3]

On 3 January 1919 agreement was reached between the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann and the Arab leader Emir Feisal. Article Four of this agreement declared that all 'necessary measures' should be taken 'to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale, and as quickly as possible to settle Jewish immigrants upon the land through closer settlement and intensive cultivation of the soil'. In taking such measures, the agreement went on, 'the Arab peasant and tenant farmers shall be protected in their rights, and shall be assisted in forwarding their economic development.'[4]

The Weizmann-Feisal agreement did not refer to Jewish statehood. Indeed, on 19 January 1919, Balfour wrote to his fellow Cabinet Minister Lord Curzon: 'As far as I know, Weizmann has never put forward a claim for the Jewish Government of Palestine. Such a claim is, in my opinion, certainly inadmissible and personally I do not think we should go further than the original declaration which I made to Lord Rothschild.'[5]

Scarcely six weeks later, on February 27, in Balfour's presence, Weizmann presented the essence of the Weizmann-Feisal Agreement to the Allied Supreme Council in Paris, telling them that the nation that was to receive Palestine as a League of Nations Mandate must first of all 'Promote Jewish immigration and closer settlement on the land', while at the same time ensuring that 'the established rights' of the non-Jewish population be 'equitably safe-guarded'.

During the discussion, Robert Lansing, the American Secretary of State, asked Weizmann for clarification 'as to the meaning of the words "Jewish National Home." Did that mean an autonomous Jewish Government?' Weizmann replied, as the minutes of the discussion record, 'in the negative'. The Zionist Organisation, he told Lansing — reiterating what Balfour had told Curzon — 'did not want an autonomous Jewish Government, but merely to establish in Palestine, under a Mandatory Power, an administration, not necessarily Jewish, which would render it possible to send into Palestine 70,000 to 80,000 Jews annually.' The Zionist Organisation wanted permission 'to build Jewish schools where Hebrew would be taught, and to develop institutions of every kind. Thus it would build up gradually a nationality, and so make Palestine as Jewish as America is American or England English.'

The Supreme Council wanted to know if such a 'nationality' would involve eventual statehood? Weizmann told them: 'Later on, when the Jews formed the large majority, they would be ripe to establish such a Government as would answer to the state of the development of the country and to their ideals.'[6]

The British Government supported the Weizmann-Feisal Agreement with regard to both Jewish immigration and land purchase. On June 19 the senior British military officer in Palestine, General Clayton, telegraphed to the Foreign Office for approval of a Palestine ordinance to re-open land purchase 'under official control'. Zionist interests, Clayton stated, 'will be fully safeguarded'.[7]

Clayton's telegram was forwarded to Balfour, who replied on July 5 that land purchase could indeed be continued 'provided that, as far as possible, preferential treatment is given to Zionist interests'.[8]

The Zionist plans were thus endorsed by both Feisal and Balfour. But on 28 August 1919 a United States commission, the King-Crane Commission, appointed by President Woodrow Wilson, published its report criticizing Zionist ambitions and recommending 'serious modification of the extremist Zionist program for Palestine of unlimited immigration of Jews, looking finally to making Palestine distinctly a Jewish State'.[9]

The King-Crane Commission went on to state that the Zionists with whom it had spoken looked forward 'to a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, by various forms of purchase'. In their conclusion, the Commissioners felt 'bound to recommend that only a greatly reduced Zionist program be attempted'; a reduction that would 'have to mean that Jewish immigration should be definitely limited, and that the project for making Palestine a distinctly Jewish commonwealth should be given up'.[10]

The United States was in a minority at the Supreme Council. On September 19 the Zionists received unexpected support from the Times, which declared: 'Our duty as the Mandatory power will be to make Jewish Palestine not a struggling State, but one that is capable of vigorous and independent national life.'[11]

Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for War, and with ministerial responsibility for Palestine, took a more cynical view of Zionist ambitions. On October 25, in a memorandum for the Cabinet, he wrote of 'the Jews, whom we are pledged to introduce into Palestine and who take it for granted that the local population will be cleared out to suit their convenience.'[12]

Churchill's critical attitude did not last long. Fearful of the rise of Communism in the East, and conscious of the part played by individual Jews in helping to impose Bolshevik rule on Russia, he soon set his cynicism aside. In an article entitled 'Zionism versus Bolshevism: the Struggle for the Soul of the Jewish People', he wrote in the Illustrated Sunday Herald on 8 February 1920 that Zionism offered the Jews 'a national idea of a commanding character'. Palestine would provide 'the Jewish race all over the world' with, as Churchill put it, 'a home and a centre of national life'.

Although Palestine could only accommodate 'a fraction of the Jewish race', but 'if, as may well happen, there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State under the protection of the British Crown which might comprise three or four millions of Jews, an event will have occurred in the history of the world which would from every point of view be beneficial, and would be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.' 'Jewish national centre' in Palestine; a centre, he asserted, which might become 'not only a refuge to the oppressed from the unhappy lands of Central Europe', but also 'a symbol of Jewish unity and the temple of Jewish glory'. On such a task, he added, 'many blessings rest'.[13]

On 24 April 1920, at the San Remo Conference, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George accepted a British Mandate for Palestine, and that Britain, as the Mandatory Power, would be responsible for giving effect to the Balfour Declaration. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, noted in his diary that there had been a 'two-hour battle' among the British and French delegates, 'about acknowledging and establishing Zionism as a separate State in Palestine under British protection'.[14]

In January 1921, Lloyd George appointed Churchill to be Secretary of State for the Colonies, charged with drawing up the terms of the Mandate and presenting them to the League of Nations. In March 1921, at the Cairo Conference, Churchill agreed to the establishment of a Jewish gendarmerie in Palestine to ward off local Arab attacks (Churchill preferred a Jewish Army). He also agreed that Transjordan, while part of the original Mandated Territory of Palestine, would be separate from it, and under an Arab ruler. This fitted in with what Britain had in mind as the wider settlement of Arab claims. On 17 January 1921, T.E. Lawrence had reported to Churchill that Emir Feisal 'agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine' in return for Mesopotamia (Iraq) — where Churchill agreed at the Cairo Conference to install him as King — and Transjordan, where Feisal 'hopes to have a recognized Arab State with British advice'.[15]

From Cairo, Churchill went to Jerusalem, where he was given a petition from the Haifa Congress of Palestinian Arabs, dated 14 March 1921, which began: '1. We refuse the Jewish Immigration to Palestine. 2. We energetically protest against the Balfour Declaration to the effect that our Country should be made the Jewish National Home.'[16] Churchill rejected the Arab arguments. 'It is manifestly right,' he announced publicly on March 28, 'that the Jews, who are scattered all over the world, should have a national centre and a National Home where some of them may be reunited. And where else could that be but in the land of Palestine, with which for more than 3,000 years they have been intimately and profoundly associated? We think it would be good for the world, good for the Jews, and good for the British Empire.'[17]

After Churchill's visit, Arab violence in Jaffa led the British High Commissioner in Palestine, a British Jew, Sir Herbert Samuel, to order an immediate temporary suspension of Jewish immigration. This did not find favor in the Colonial Office. A telegram drafted for Churchill by one of his senior advisers, Major Hubert Young, who during the war had played his part in the Arab Revolt, was dispatched to Samuel on May 14. 'The present agitation', the telegram read, 'is doubtless engineered in the hope of frightening us out of our Zionist policy... We must firmly maintain law and order and make concessions on their merits and not under duress.'

On June 22 Churchill explained the British position on Zionism at a meeting of the Imperial Cabinet. The Canadian Prime Minister, Arthur Meighen, questioned Churchill about the meaning of a Jewish 'National Home'. Did it mean, Meighen asked, giving the Jews 'control of the Government'? To this Churchill replied: 'If, in the course of many years, they become a majority in the country, they naturally would take it over.'[18]

Churchill was asked about this sixteen years later by the Palestine Royal Commission. 'What is the conception you have formed yourself,' he was asked, 'of the Jewish National Home?' Churchill replied: 'The conception undoubtedly was that, if the absorptive capacity over a number of years and the breeding over a number of years, all guided by the British Government, gave an increasing Jewish population, that population should not in any way be restricted from reaching a majority position.' Churchill went on to tell the Commission: 'As to what arrangement would be made to safeguard the rights of the new minority' — the Arab minority — 'that obviously remains open, but certainly we committed ourselves to the idea that someday, somehow, far off in the future, subject to justice and economic convenience, there might well be a great Jewish State there, numbered by millions, far exceeding the present inhabitants of the country and to cut them off from that would be a wrong.' Churchill added: 'We said there should be a Jewish Home in Palestine, but if more and more Jews gather to that Home and all is worked from age to age, from generation to generation, with justice and fair consideration to those displaced and so forth, certainly it was contemplated and intended that they might in the course of time become an overwhelmingly Jewish State.'[19] Whether the Jews could form a majority — the sine qua non of statehood — was challenged publicly by Herbert Samuel on 3 June 1921, when he said that 'the conditions of Palestine are such as not to permit anything in the nature of mass immigration'.[20] But at a meeting in Balfour's house in London on July 22, Lloyd George and Balfour had both agreed 'that by the Declaration they had always meant an eventual Jewish State'.[21] Churchill's adviser, Major Young, likewise favored a policy that, he wrote to Churchill on August 1, involved 'the gradual immigration of Jews into Palestine until that country becomes a predominantly Jewish State'. Young went on to argue that the phrase 'National Home' as used in the Balfour Declaration implied no less than full statehood for the Jews of Palestine. There could be 'no half-way house', he wrote, between a Jewish State and 'total abandonment of the Zionist programme'.[22] When the Cabinet met on August 17 there was talk of handing the Palestine Mandate to the United States, but Lloyd George rejected this. The official minutes noted: 'stress was laid on the following consideration, the honor of the government was involved in the Declaration made by Mr Balfour, and to go back on our pledge would seriously reduce the prestige of this country in the eyes of the Jews throughout the world'.

On 3 June 1922 the British Government issued a White Paper, known as the Churchill White Paper, which stated: 'So far as the Jewish population of Palestine are concerned it appears that some among them are apprehensive that His Majesty's Government may depart from the policy embodied in the Declaration of 1917. It is necessary, therefore, once more to affirm that these fears are unfounded, and that that Declaration, re-affirmed by the Conference of the Principal Allied Powers at San Remo and again in the Treaty of Sèvres, is not susceptible of change.' The White Paper also noted: 'During the last two or three generations the Jews have recreated in Palestine a community, now numbering 80,000... it is essential that it should know that it is1

in Palestine as of right and not on the sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a Jewish National Home in Palestine should be internationally guaranteed, and that it should be formally recognized to rest upon ancient historic connection.'[23]

To reinforce this concept of 'right', Churchill had granted the Zionists a monopoly on the development of electrical power in Palestine, authorizing a scheme drawn up by the Russian born Jewish engineer, Pinhas Rutenberg, to harness the waters of the Jordan River. To stop what critics were calling the 'beginning of Jewish domination', a debate was held in the House of Lords demanding representative institutions that would enable the Arabs to halt Jewish immigration. In the debate, held on June 21, sixty Peers voted against the Mandate as envisaged by the White Paper, and against the Balfour Declaration. Only twenty-nine Peers voted for it.

On July 4 it fell to Churchill to persuade the House of Commons to reverse this vote. He staunchly defended the Zionists. Anyone who had visited Palestine recently, he said, 'must have seen how part of the desert have been converted into gardens, and how material improvement has been effected in every respect by the Arab population dwelling around.' Apart from 'this agricultural work — this reclamation work — there are services which science, assisted by outside capital, can render, and of all the enterprises of importance which would have the effect of greatly enriching the land none was greater than the scientific storage and regulation of the waters of the Jordan for the provision of cheap power and light needed for the industry of Palestine, as well as water for the irrigation of new lands now desolate.' The Rutenberg concession offered to all the inhabitants of Palestine 'the assurance of a greater prosperity and the means of a higher economic and social life'.

Churchill asked that the Government be allowed 'to use Jews, and use Jews freely, within limits that are proper, to develop new sources of wealth in Palestine'. It was also imperative, he said, if the Balfour Declaration's 'pledges to the Zionists' were to be carried out, for the House of Commons to reverse the vote of the House of Lords. Churchill's appeal was successful. Only thirty-five votes were cast against the Government's Palestine policy, 292 in favour.[24]

The way was clear for presenting the terms of the Mandate to the League of Nations. On July 5, Churchill telegraphed Sir Wyndham Deedes, who was administering the Government of Palestine in Samuel's absence, that 'every effort will be made to get terms of Mandate approved by Council of League of Nations at forthcoming session and policy will be vigorously pursued'.[25] On 22 July 1922 the League of Nations approved the Palestine Mandate (it came into force on 29 September 1923). One particular article, Article 25, relating to Transjordan, disappointed the Zionists, who had hoped to settle on both sides of the Jordan River. 'In the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined', Article 25 stated, 'the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those conditions, provided that no action shall be taken which is inconsistent with the provisions of Articles 15, 16 and 18.' 32

The Zionists pointed out that Article 15 was clearly inconsistent with not allowing a Jewish presence in Transjordan, for it stated clearly, with regard to the whole area of Mandatory Palestine, west and east of the Jordan, that 'The Mandatory shall see that complete freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship, subject only to the maintenance of public order and morals, are ensured to all. No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief. The right of each community to maintain its own schools for the education of its own members in its own language, while conforming to such educational requirements of a general nature as the Administration may impose, shall not be denied or impaired.'

The rest of the Mandate was strongly in support of Zionist aspirations. Article 2, while making no reference to the previous four and a half years' debate on statehood, instructed the Mandatory to secure 'the development of self-governing institutions'. In a note to the United States government five months later, the Foreign Office pointed out that 'so far as Palestine is concerned' Article 2 of the Mandate 'expressly provides that the administration may arrange with the Jewish Agency to develop any of the natural resources of the country, in so far as these matters are not directly undertaken by the Administration'. The reason for this, the Foreign Office explained, 'is that in order that the policy of establishing in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people could be successfully carried out, it is impractical to guarantee that equal facilities for developing the natural resources of the country should be granted to persons or bodies who may be motivated by other motives'. [26] It was on this basis that the Rutenberg electrical concession had been granted as a monopoly to the Zionists, and on which representative institutions had been withheld for as long as the Arabs were in a majority.

Article 4 recognized the Zionist Organization as the 'appropriate Jewish Agency', to work with the British Government 'to secure the co-operation of all Jews who are willing to assist in the establishment of a Jewish national home'. Article 6 instructed the Palestine Administration both to 'facilitate' Jewish immigration, and to 'encourage' close settlement by Jews on the land, 'including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes'.[27]

On the evening of 22 July 1922, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the pioneer of modern spoken Hebrew, went to see his friend Arthur Ruppin. It was more than forty years since Ben Yehuda had come to live in Palestine. He had just seen a telegram announcing that the League of Nations had just confirmed Britain's Palestine Mandate. 'The Ben Yehudas were elated,' Ruppin recorded in his diary, with Ben Yehuda telling Ruppin, in Hebrew, 'now we are in our own country.' Ruppin himself was hesitant. 'I could not share their enthusiasm,' he wrote. 'One is not allocated a fatherland by means of diplomatic resolutions.' Ruppin added: 'If we do not acquire Palestine economically by means of work and if we do not win the friendship of the Arabs, our position under the Mandate will be no better than it was before.'[28]

Footnotes to Martin Gilbert's article

1 Council of the League of Nations, League of Nations Permanent Mandates Commission, 22 July 1922: League of Nations − Official Journal.

2 War Cabinet minutes, 30 October 1917; Cabinet Papers, 23/4.

3 Foreign Office papers, 371/3054.

4 The text of the Weizmann-Feisal Agreement was quoted in the Times, 10 June 1936.

5 Curzon papers, India Office Library.

6 Supreme Council minutes: Event 4651: Zionist presentation to the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference.

7 Foreign Office papers, 371/4171.

8 ibid.

9 Henry C. King was a theologian and President of Oberlin College, Ohio Charles R. Crane was a prominent Democratic Party contributor who had been a member of the United States delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

10 Report of American Section of Inter-Allied Commission of Mandates in Turkey: An official United States Government report by the Inter-allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey. American Section. First printed as 'King-Crane Report on the Near East', Editor and Publisher: New York, 1922, Editor and Publisher Co., volume 55.

11 the Times, London, 9 September 1919.

12 Churchill papers, 16/18.

13 Illustrated Sunday Herald, 8 February 1920.

14 Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, diary (unpublished).

15 Churchill papers, 17/20.

16 ibid.

17 ibid.

18 Minutes of the Imperial Cabinet: Lloyd George papers.

19 Palestine Royal Commission, notes of evidence, 12 March 1937: Churchill papers: 2/317.

20 Samuel papers.

21 Weizmann papers.

22 Colonial Office papers, 733/10.

23 Statement of British Policy in Palestine, Command Paper 1700 of 1922, 3 June 1922.

24 Hansard, Parliamentary Debates, 4 July 1922.

25 Colonial Office papers, 733/35.

26 Communication dated 29 December 1921, Command Paper 2559 of 1926.

27 Council of the League of Nations, League of Nations Permanent Mandates Commission, 22 July 1922. League of Nations − Official Journal.

28 Arthur Rupin diary, Rupin papers.

Return to End Notes Listed By AuthorConnor Cruise O'Brien: The Siege. P140, P149, P151, P158, P194, P263.

This book provides us with information on the reactions to the 1922 White Paper and the emergence of Transjordan. When the Arabs protested, the Colonial Office told them, "It is essential that the Jewish community should know that it is in Palestine as of right and not on sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a Jewish National Home should be internationally recognized and that it should be formally recognized to rest upon ancient historical connections." The Arabs were reassured that the British did not mean a Jewish State. The White Paper did not say that immigration would be governed by the "absorptive capacity" of the country until many years later. Curzon who replaced Churchill in the British Foreign office was quick to remark, "I think the entire concept wrong. Here is a country with 580,000 Arabs and 30,000 or is it 60,000 Jews [by no means all Zionists]. Forgotten were the words of Lord Robert Cecil in 1918, "Our wish is that the Arabian countries shall be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians and Judea for the Jews." Nor those of Lloyd George, "No race had done better out of the fidelity with which the Allies redeemed their promises to the opposed races than the Arabs. Owing to the tremendous sacrifices of the Allied Nations, and more particularly of Britain and her Empire, the Arabs have already won independence in Iraq, Arabia, Syria and Trans-Jordan, although most of the Arab races fought [for Turkey]...The Palestinian Arabs fought for Turkish rule."

Jabotinsky's position, "The aim of Zionism is the formation of a Jewish majority in Palestine on both banks of the Jordan" and Weizmann's response, "I have no understanding nor sympathy with the demand of a Jewish majority in Palestine. A majority does not guarantee security, a majority is not essential for the development of a Jewish civilization and culture. The world will interpret the demand for a Jewish majority that we want to achieve it, in order to drive the Arabs from the country."

On the one hand, Herbert Samuel is attributed to saying in a promise that in the event of a successful termination of the war [WW1], Palestine would be given to the Jews. On the other hand, according to O'Brien, the British Foreign Secretary at the time, Ernest Bevin expressed himself callously with, "Jews must not try to get to the head of the queue." O'Brien questions British inconsistent behavior and concludes that unrestricted Jewish immigration and partition, would set the Arab world, and the Muslim world, ablaze," In fact, consistently, the British continued to favor exclusive Arab development east of the Jordan River by enacting restrictive regulations against the Jews, even when Arab leaders sought Jewish involvement in the development of Transjordan.

Those who had any tendency to romanticize Arabs called the Palestinians "so-called Arabs", as did Curzon. He had disliked the idea of the Jewish National Home from the beginning and in 1920, when he was helping to build it, he seems to have disliked it more than ever. At the same time, as reported by Christopher Sykes, Winston Churchill "wished Zion well from his heart". Having set up a Middle East Department in the Colonial Office, Churchill convened a conference of senior British officials in Cairo, in order to reach a settlement with the leaders of Arab nationalism." Churchill explained that Faisal was to be king of Iraq, and suitably "elected". Abdullah was to be emir of Transjordan, a kingdom to be made for him by detaching the whole territory east of the Jordan from the rest of Mandate Palestine. From Cairo, Churchill went onto Palestine, where, in spite of these concessions to "Arab nationalism", he was welcomed by the Jews and largely boycotted by the Arabs. P140, 149, 151, 158, 194, 263.

In terms of perspective, the 1992 White Paper [also referred to as the Churchill White Paper] was the first official manifesto interpreting the Balfour Declaration. It was issued after the investigation into the 1921 disturbances. Although the White Paper stated that the Balfour Declaration could not be amended and that the Jews were in Palestine by right, the British partitioned the area of the Mandate by excluding the area of the Mandate by excluding the area east of the Jordan River from Jewish settlement. That land, 76% of the original Palestine Mandate land, was renamed Transjordan and was given to the Emir Abdullah by the British.

According to Sir Alec Kirkbride, the British representative in the area, Transjordan was "... intended to serve as a reserve of land for use in the resettlement of Arabs once the National Home for the Jews in Palestine, which [Britain was] pledged to support, became an accomplished fact. There was no intention at that stage of forming the territory east of the River Jordan into an independent Arab State." [10]

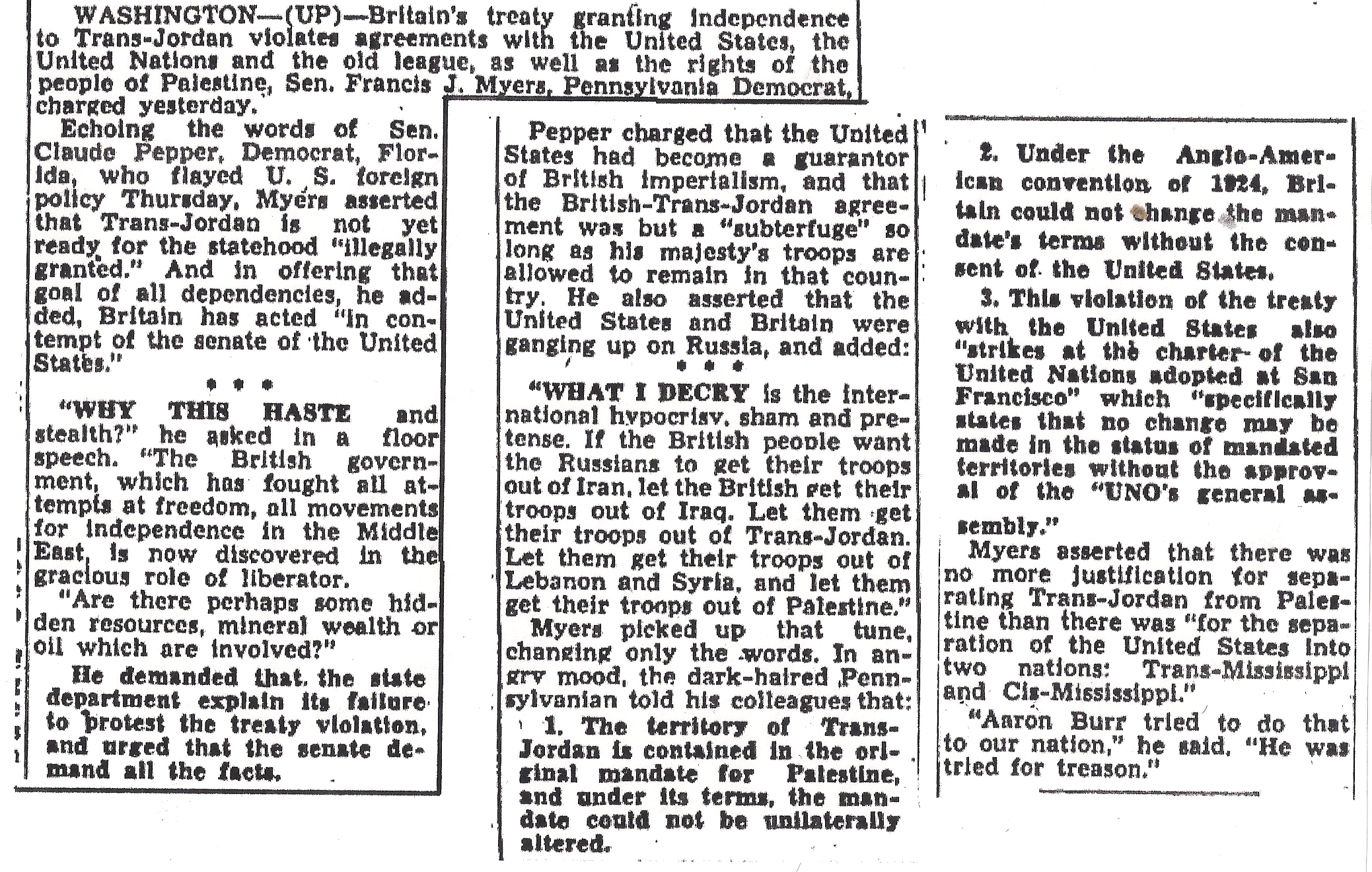

As an example of the world wide non-acceptance of the proclamation on Transjordan, an interesting report featuring vocal outbursts by two US Senators appeared in the St. Petersburg Times:

Raphael Medoff. Zionism And The Arabs: An American Jewish Dilemma, 1898-1948. PP40-42.

In this rather curious book, Raphael Medoff explores the reactions of American Jews and Associations in Chapter 2, including the British behavior as related to Transjordan. The insights are as applicable today as they were during the given period. The devastating Arab riots in 1929, in which 133 Jews were killed and the Chevron Jewish community that was decimated, elicited an astonishing array of apologetics from American Jews, whose mirage of Arab-Zionist amity had suddenly vanished. To be sure, Jews in Palestine had responded like brave New England pioneers confronting Indians. But they were nonetheless blamed for inciting the Arabs. Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner at the time, reacted by "briefly halting Jewish immigration to the Holy Land and assuring Palestinian Arabs that His Majesty's Government would not 'impose upon them' anything that conflicted with their religions, political and economic interests".

"Although the San Remo conference in 1920 had approved England's rule over both Palestine and Transjordan as a single unit, with the Balfour Declaration to apply throughout, the League of Nations decided in 1921, at London's urging to give Britain the right to withhold application of Balfour's terms from the Jordanian territory. From Britain's point of view, it was a matter of balancing its interest in developing a friendly Jewish national entity in [part of] Palestine and its desire to maintain alliances with the Arab world.

From the Zionist point of view, the English failure to prevent the Arab riots, the findings of the Haycraft commission, and the severing of Transjordan all pointed to a creeping British estrangement from the spirit of the Balfour Declaration. The Zionists were correct in their perception that a shift in Britain's Palestine policy was underway. Despite the drop in violence from 1922-1929, on the propaganda battlefront, there was no escaping the proliferation of public challenges to Zionism on the issue of majority rights in Palestine. The riots of 1920 -1921 put a new weapon in the arsenal of Zionism's critics.

Return to End Notes Listed By AuthorSidney Zion.

The Palestine Problem: It's All In A Name. August 2, 2003.

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/956936/posts.

Originally printed in

http://www.jewishpress.com/news_article_print.asp?article=2674.

July 31, 2003. (not available).

The only thing about the Middle East that goes without argument and even without saying is that the Palestinian Arabs are a stateless, homeless people.

You can't pick a fight on that anywhere in the world. The fact that four wars have been fought for the ostensible purpose of resolving the plight of the Palestinians has solidified this consensus. Everyone believes it.

The Oslo peace process lies in ruin, and the road map plan is off to a shaky start, due to the inability of the parties involved to agree on a formulation of principles concerning the right, or lack thereof, of the Palestinians to determine their own future on the West Bank of the river Jordan — the area universally regarded as the historic, political, geographic, and demographic landmass of Palestine.

But even as the arguments rage over whether or how this should or can be accomplished — a state, a homeland, an entity? — a lot of well-intentioned people will tell you that there is not now and never has been a Palestinian nation. The problem with this notion is that it is not true. There is and has been a Palestinian nation since May 14, 1946 — only two years to the day before there was an Israeli nation.

Originally called the Kingdom of Transjordan, that nation is now the Kingdom of Jordan. It lives on the East Bank of the Jordan River and comprises 80 percent of the historic, political, geographic, and demographic landmass of Palestine. It has a population of three million people, virtually all of whom were either born there or arrived there from the other 20 percent of Palestine — Israel plus the 'occupied territories' known as the 'West Bank'.

Palestine, then, includes both sides of the Jordan River, bounded on the west by the Mediterranean, on the east by Saudi Arabia and Iraq, on the south of Egypt, on the north by Syria and Lebanon.

These boundaries were universally acknowledged from the end of World War I until 1946, when Great Britain created by fiat the independent Kingdom of Transjordan — thus lopping off four- fifths of Palestine and handing it to the Arabs, in direct violation of the mandate over the territory granted to Great Britain by the League of Nations.

In the years since, Jordan has been recognized as a nation separate and apart from Palestine, its only connection being its role as the principal 'host country' for Palestinian refugees displaced by the creation of Israel.

While Israel won its independence through revolution against the British colonialists, it is viewed as a creature of the United Nations, owing its existence to a world guilt-ridden over the Holocaust.

Since its victory in the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel — it is said — now controls the whole of Palestine. Its refusal to cede completely the territory occupied after that war — from East Jerusalem to the Jordan River, plus the Gaza Strip — is therefore considered the bar to national rights or 'self-determination' of the Palestinian Arabs.

So goes the conventional wisdom of much of the world, and, because it is so widely believed, it is naturally thought to be fair and objective. No matter that it is based on an incredible distortion of history, politics, geography, and demography.

Yet, unless this distortion is corrected, there is little hope for anything close to enduring Middle East peace. A brief look at relatively recent events puts the problem in perspective.

A Gift For Abdullah

Before World War I, the word 'Palestine' had no clear-cut geographical denotation and represented no political identity. In 1920, however, the Allied powers conferred on Great Britain a 'mandate' over the territory formerly occupied by Turkey. It was called the Palestine Mandate and included the land on both sides of the Jordan River.

This mandate was confirmed by the League of Nations in 1922 and remained unchanged during the League's lifetime.

The mandate incorporated the Balfour Declaration, the famous 1917 proclamation by which Great Britain committed itself to provide a homeland in Palestine for the Jewish people; it did not provide a homeland for the Arabs living there, but it did protect their 'civil and religious,' although not their political, rights.

However, two months after the League of Nations approved the mandate, Winston Churchill, then Britain's colonial secretary, changed the rules of the game.

"One afternoon in Cairo," as Churchill later boasted, he simply took all the land east of the Jordan River and inserted the Hashemite Abdullah — the great-grandfather of the present King Abdullah — as its emir.

But he did not free it from the mandate, and the people living on the East Bank were in all respects Palestinians. The people living there traveled under Palestinian passports, as did the Jews and Arabs living on the West Bank. But the whole country was effectively ruled by Britain.

Why did Churchill do it? Because Abdullah was bitterly disappointed that he hadn't been chosen by the British as king- designate of Iraq — a post that went to his brother. Churchill wanted to stroke Abdullah's ego and at the same time serve the empire.

But, according to Britain's East Bank representative, Sir Alec Kirkbride, this land, constituting 80 percent of the mandate, was "intended to serve as a reserve of land for use in the resettlement of Arabs once the National Home for the Jews in Palestine, which they were pledged to support, became an accomplished fact. There was no intention at that stage of forming the territory east of the river Jordan into an independent Arab state."

Indeed, Churchill persuaded the Zionists to go along with the suspension of Jewish immigration to the East Bank on the grounds that this would mollify the indigenous Arab population on the West Bank — then 200,000 strong — and thus make possible a Jewish homeland west of the Jordan.

Of course, it did no such thing; instead, it whetted Arab appetites for the whole of Palestine, an objective which was nearly achieved several time: the Palestinian Arab uprising against the Jews in 1936; the British White Paper of 1939, which cut off the Jewish immigration to the Holy Land, locking European Jews in with Hitler; and the united Arab war against the newly proclaimed State of Israel in 1948.

Reversing Balfour

Until 1946, however, Transjordan remained under the British Palestine Mandate. The English declared Transjordan an independent entity without a soupcon of international authority.

As a result, what began in 1920 as a mandate to turn Palestine into a Jewish homeland turned into a reverse Balfour Declaration, creating an Arab nation in four-fifths of Palestine and leaving the Jews to fight for statehood against the Arabs on the West Bank.

The upshot: Jordan is now considered an immutable entity, as distinct from Palestine as are Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

But a country whose population is virtually all Palestinian can hardly be considered as something less than a Palestinian nation.

Still, the notion that Jordan has nothing to do with Palestine is so deeply embedded that it comes as no real surprise that The New York Times and the rest of the media elite treat it as a world apart.

This is hardly something new, of course; readers of a certain age and long memory may recall that the Times took this approach as least as far back as the mid-1970's when, in a three- part series on the Palestinians, the paper drew historical maps cutting Transjordan out of the British mandate — and repeated the fiction that Israel occupied the whole of Palestine.

Ironically, while the Times was breast-beating over the 'stateless' Palestinians, the late left-wing journalist I.F. Stone was complaining in the New York Review of Books that Jewish dissidents, like himself, could not get a word in edgewise in behalf of Palestinian nationhood.

Stone knew all about the two banks of the Jordan, as his piece indicated. It seems, however, that it didn't register with him; he suggested neither that the Palestinians already have a state nor that the one thing the American press never reports is the fact that Jordan is Palestine.

On the other hand, the Israeli government doesn't say it either, and a story goes with that fact.

Jordan Vs. Palestine

When the Zionists agreed in 1922 to suspend immigration to the East Bank, in accordance with Churchill's request, Vladimir Jabotinsky signed on.

But Jabotinsky — the elegant, fiery Zionist leader who later became the father of the underground Irgun Zvai Leumi and the 'eagle' of its commander, Menachem Begin — changed his mind about the deal a year later after it became clear that the Jews had traded away most of the mandate for nothing.

The Establishment Zionists, however, stuck with the British ever after.

"There are no Palestinians, there are only Jordanians," said Golda Meir again and again. Of course, she was wrong. In fact, there are no Jordanians, only Palestinians. One reason why Golda insisted on the opposite — as everyone with a passing knowledge of Zionist politics understands — was that her political enemy Jabotinsky was on the other side.

Meir and her Mapai party, which ruled Israel from the pre-state days until Begin was elected prime minister in 1977, hated Jabotinsky and his followers,

considering them all 'fascists.'

The Jabotinsky vision held that both sides of the Jordan belonged to Israel; he wrote a song about it: "The West Bank is ours, and the East Bank is ours."