JIHAD ELSENWHERE

by Olivier Guitta

Part 1: Tunisia. Where Spring Was Sprung

it is less than three years since the fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in the small Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, sparking the events that toppled dictator Ben Ali and launched the "Arab Spring." Now, the high hopes of those days have faded, and Tunisia is in disarray, its society deeply divided and violence flaring.

On July 25, leading opposition member of parliament Mohamed Brahmi was shot 14 times in front of his house. The assassins used the same weapon that had been used to kill another opposition figure, Chokri Belaid, in February. The families of both victims put the blame squarely on Ennahda—the Muslim Brotherhood party in power since elections in October 2011—and its founder and leader, Rachid Ghannouchi. Outrage over the killings led to violence in several towns. Increasingly, the demonstrators' calls for Ennahda to step down are being echoed among the political elite.

Demonstrations are drawing larger and younger crowds—some 50,000 people filled the streets of Tunis on August 6, the most since the revolution—and the protesters' signs and chants are increasingly violent and personal: "Ghannouchi is a murderer!" The police respond with brutal repression. As longtime opposition journalist Taoufik ben Brik put it, "The post-Ennahda period has already begun. Not without Ennahda, but rather under Ennahda."

At present, 82 of the 217 members of parliament are boycotting the assembly to protest Ennahda's rule. One of them, Karima Sould, said, "The assassination of one of ours has come as an electric shock. It's now or never. [Ennahda] got us with Belaid. We won't be had twice." Two camps—Islamist and anti-Islamist—are facing off, and the climate of hatred is such that at any moment a spark could ignite the country. Whether Ghannouchi will learn anything from the ouster of his "Brothers" in Egypt remains to be seen, but his hardline statements suggest he hasn't so far.

Also unclear at this writing is what action will be taken by the UGTT, a 750,000-strong trade union (in a country of 10 million) known as "El Makina" (the machine), which plays a role in Tunisian affairs sometimes likened to that of the army in Egypt. The UGTT was the driving force behind Ben Ali's fall and could very well take the lead in turning Ennahda out. Polls suggest that public support for Ennahda is collapsing (Gallup put approval for the party at 32 percent in May, down from 56 percent in March 2012). And the economy is in a disastrous state. On August 16, Standard & Poor's downgraded Tunisia's credit rating (for the second time this year) to B.

As for national security, a Tunisie Sondage poll conducted in early August found that 65 percent of Tunisians considered the terrorist threat high, and 74 percent blamed it on Ennahda's lenience towards jihadists. Until a recent falling out, Ennahda maintained close relations with Salafist groups, notably Ansar al Sharia. It is a member of that group, convicted terrorist Boubakeur el-Hakim, who is suspected of both high-profile assassinations this year. A French citizen who grew up in the suburbs of Paris, Hakim was convicted by a French court in 2008 of recruiting French jihadists to fight in Iraq, but he was released from prison in 2011. In addition, the Ennahda government has ceded control of dozens of mosques to jihadists, who have used them to recruit extensively.

Alaya Allani, a leading historian of Islamism and professor at Manouba University near Tunis, estimates that the number of jihadists in the country has rocketed from 800 a year ago to some 3,000-4,000 today. The Salafist wing of Ennahda has steadily reached out to jihadists for both ideological and opportunistic reasons. And the leading terrorist organization in the region, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), as long ago as October 2012 embraced Ennahda's goal of implementing sharia in Tunisia.

Now AQIM is making its presence felt. On July 30, AQIM militants savagely murdered nine Tunisian soldiers on the Algerian-Tunisian border. Some AQIM operatives, veterans of the fight in Mali, are joining forces with Tunisian Salafists kicked out of Syria. Even though the Algeria-Tunisia border is formally closed, it is far from sealed, and Algerian extremists are helping their Tunisian counterparts manufacture IEDs. Furthermore, Algeria has refused to cooperate with the Islamist regime in Tunisia because of its Salafist elements. It took no one by surprise when a terrorist blew himself up on August 2 while building a bomb in a suburb of Tunis.

Between domestic unrest and the deliberate meddling of jihadists from abroad, Tunisia is poised for continuing and possibly explosive instability.

Part 2: Algeria and Its Islamists. A presidential succession fraught with peril.

Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika returned to Algiers on July 16 after three months in a hospital in Paris. His health will prevent him from running for reelection in April, and it's unclear whether he can run the country until then. As a result, the contest over his succession is already gearing up, and the Islamists are first out of the starting blocks. The United States and the European Union—along with China, a major presence in energy-rich Algeria—are closely monitoring this latest round in the continuing struggle over the Islamists' role in government and society.

In Algeria, officials celebrate the opening of a section of a Chinese-built east

In Algeria, officials celebrate the opening of a section of a Chinese-built east-west expressway (Newscom)

Bouteflika is widely seen as the counter to the Islamists. In office since 1999 and reelected in 2009 with a Soviet-style 90 percent of the vote, he presided over the end of the bloody civil war unleashed by a military coup after the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) won parliamentary elections in December 1991. The war killed as many as 200,000 people. Though the Islamists suffered a military defeat, the creeping Islamization of Algerian society has proceeded apace.

Oddly enough, the regime has regarded this trend with complacency. It has even courted conservative Muslim Brothers and named a prime minister sympathetic to the Islamists, Abdelaziz Belkhadem, who served from 2006 to 2008. Belkhadem closed down outlets selling alcoholic beverages, condemned those who broke the fast during Ramadan, hunted illicit couples, and supported restaurants that refused to serve unescorted females. He even called the Koran "the only constitution of Algerian society," echoing the motto of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Now, in the hope of a political comeback, the three main Islamist parties have united in a "Green Alliance" around a single presidential candidate. While some regard these groups as "Islamist in name only" because they are participating in the political process and are somewhat close to the elite, the powers that be are not ready to allow their candidate to become president.

The more dangerous Islamists are sitting out the election. They include the FIS and Salafist groups that do not control a large number of mosques around the country. Abassi Madani, a founder of the FIS who was imprisoned, then under house arrest, from 1991 to 2003, is stirring the pot from Qatar, where the emir gives him a monthly stipend of $15,000. Madani is calling for the legalization of the FIS. This probably won't happen, but agitating for it allows him to present himself as a victim of an anti-Muslim dictatorship.

Most likely, the army and the old guard will choose the next president. In an attempt to quell the anger of the street, the regime dispenses largesse. In 2011, for example, it provided some $23 billion in public grants and retroactive salary and benefit increases for public workers.

After the In Amenas terrorist attack in January—when al Qaeda-linked militants took some 800 workers and others hostage at a remote gas facility near the Tunisian border and some 70 people were killed before Algerian security forces had retaken the plant—Western governments realized that they needed to act to protect their interests in Algeria. This was even truer for China, which has a huge stake in Algeria's future.

In recent years, China has reaped the benefits of ties to Africa dating back to Mao's support for anti-colonial revolutionary movements in the middle of the last century. And Algeria hosts what may be the largest Chinese community on the continent, estimated at up to 100,000 people. According to the daily El Khabar, 567 Chinese-owned companies now operate in Algeria. While Chinese have invested in many sectors of the economy, construction surpasses them all: Close to $15 billion in construction contracts has been awarded to Chinese firms since 2000. Under a single contract for the construction of a huge mosque in Algiers, the China State Construction Engineering Corporation required that at least 10,000 workers be flown in from China.

The relationship also entails military cooperation. Algeria has commissioned the China Shipbuilding Trading Company to supply three light frigates, and in April for the first time, the Chinese fleet docked at an Algerian port and the two countries' navies took part in joint exercises.

The Chinese "invasion" has come at a cost. Anti-Chinese sentiment is common, and riots have targeted Chinese nationals; in 2009, dozens were injured and Chinese shops were looted in Algiers. In addition, some Algerians see China as anti-Muslim because of its harsh treatment of its Muslim Uighur community; Islamist parties have lodged protests with the Chinese embassy. Even Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the main terror outfit in the region, has warned China about potential attacks on its interests and citizens. Already in 2009, AQIM ambushed a convoy of Chinese workers being escorted to a job site 100 miles southeast of Algiers, and at least 24 police officers and one civilian were killed.

For the time being, Beijing has asked Algerian authorities to protect its nationals from both terrorism and rioting. But especially if Islamist influence continues to grow, it would be surprising if China did not also increase its own ability to project force in the region in the interests of its citizens and investments. That too is a development the West should be watching.

Part 3: Rising stakes for the US in Mali

By early 2013, the continuing expansion of jihadist and Salafist groups in the northern part of the country transformed Mali into "Malistan."

In such a context, in January 2013, the West and in particular France had no choice but to intervene military to face off with the jihadists. Holding elections the last week of July was a huge successful bet that unfortunately will not alleviate the country's problems.

On July 28, successful elections took place in Mali with an unusually high turnout of about 50 percent. Democracy has been brought back to life in a chaotic time, not a small achievement indeed. In a way, the fact that Ibrahim Boubacar Keita got to first place in the race is less important than the symbolism of it all.

Also, no terror attacks occurred despite the fact one of the main terror outfits in the region, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), had threatened to carry out attacks during Election Day.

The French intervention has been very successful in retaking ground and killing jihadists such as Abu Zeid, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)'s leader in the region. Most jihadists have taken refuge in either Libya or Tunisia.

But it is just a matter of time before the jihadists start their usual asymmetrical war tactics. They will also wait until foreign troops start leaving the country to reclaim territory. Therefore, the terrorism issue is still very much alive.

But that is not all. Troubling signs are emerging that could dramatically affect Mali's future. Indeed, Mali is still a very much divided country between Islamists and secularists, and the war has left indelible scars. Also another factor at play is that the population holds a grudge against the Tuaregs for their alliance with the Jihadists.

The Tuaregs, a 200,000-strong Berber group, whose main military group, The Alliance, had been fighting the Malian regime for decades, decided to join forces with the Jihadists — something that could not be easily forgiven by a population that suffered tremendously at their hands. Interestingly, the Tuaregs have threatened to restart their insurrection if autonomy in the North was not granted to them.

Another worrisome fact is that Mali has also undergone a major seismic shift towards radicalization. In fact, starting in the 1950's, Saudi Arabia began investing in the country, from madrasas to cultural centers to clinics and pharmacies.

Still today, Saudi funding helps build prayer halls, orphanages, bridges and roads in northern Mali. For instance, clinics are a hit because of their reduced fees. In a poor country where this kind of infrastructure was lacking, the Wahhabi investment had and still has a lasting effect.

Just in Bamako there are over 3,000 madrasas and between 25 percent and 40 percent of Malian children attend them where the teaching is done in Arabic rather than in the usual French. The concerning aspect of this phenomenon is that madrasas are out of reach of the government's control, are free to teach whatever they deem advisable and, little by little, are creating generations of Wahhabis.

At the same time, Wahhabis went on a building spree of mosques up to the point where Mali, a country with 13 million people, 90 percent of whom are Muslims, counts now 17,500 registered mosques. Also in the past decade, the number of Islamic organizations has soared from just a few to over 150 now, including the very powerful international Dawa al-Islamiyya.

Hundreds of Malians have been invited to get their religious education in the Gulf and come back home radicalized and ready to convert their fellow Muslims to their Wahhabi views. Since 2001, worrying signs are emerging and fundamentalism is making inroads like never before in a moderate country such as Mali.

Photos of Osama Bin Laden are flourishing in stalls at the Bamako market and the number of radio stations preaching radical Islam is exploding. At this point, secularists are complaining that this phenomenon is pushing religious conservatism within Malian society.

Mali is far from out of the woods yet. Numerous issues need to be tackled quickly in order to reestablish the pre-2012 situation. It also may be high time for the West to realize that Mali is still very much a powder keg and that getting it right should be a priority.

Part 4: Europe's half-way ban on Hezbollah won't please anybody

After more than a decade of intense debate, the European Union has finally agreed to include Hezbollah on its list of terrorist organizations. This came about after the Bulgarian authorities revealed that Hezbollah was behind the Burgas bus bombing in July 2012, which killed six and injured 32. The fact that Hezbollah soldiers have been active in the Syrian conflict alongside Bashar al Assad's Syrian army put additional pressure on the EU to act.

While the decision constitutes a significant diplomatic achievement — having 28 countries agree unanimously on applying the t-word to Hezbollah — the move may turn out to be merely symbolic: The EU has banned only the military wing of Hezbollah rather than the whole organization.

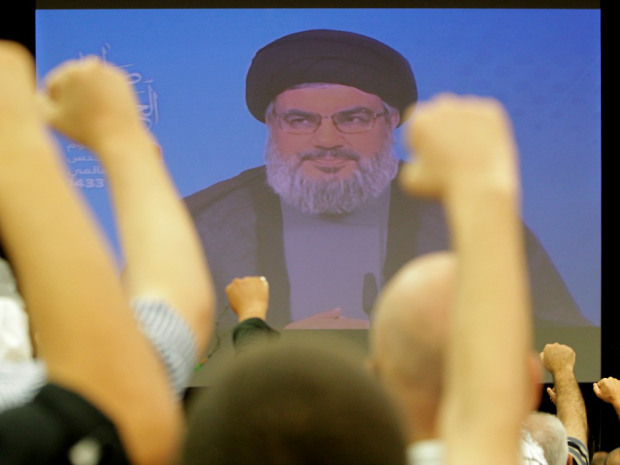

While some terror groups differentiate their military wing from their political activities, by operating under two different names, Hezbollah does not even bother with that. Its political and military aspects are really two sides of the same coin. Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah's supreme leader, is as much the "commander in chief" of Hezbollah as its "president."

In fact, it is foreigners, not Hezbollah, who often insist on making the distinction. In May 2004, for example, the French ambassador to the United States, Jean-David Levitte, declared that Hezbollah served mostly as a "social" organization. France insisted that since Hezbollah is a political party, declaring it a terrorist organization could destabilize Lebanon.

Hezbollah fundraising in Europe likely will go on unabated because the group can always hide behind its political wing. For instance, in Berlin's Neukoeln district, where one sometimes sees the green Hezbollah flag flying outside homes, people within the Shia community could still give money to Hezbollah with little fear of consequences. They can simply claim the donations are made in regard to Hezbollah's political and social activities.

With this half-baked decision, the EU won't really please anyone: It did not truly clamp down on Hezbollah, and at the same time it may have angered the Shia terror group and some within the Lebanese political class. Hezbollah might even retaliate by attacking UNIFIL soldiers in Southern Lebanon or target European interests around the world.

Gerard Araud, the current French Ambassador to the United Nations, once said that putting Hezbollah on Europe's terrorism list would be seen by some in the Arab world as "an American-Zionist plot" — and France "does not want to give them that pleasure." Yet the European Union may actually have done just that, with little benefit in return.

Olivier Guitta is the Director of Research at the Henry Jackson

Society, a Foreign Affairs think tank in

London. Contact him by email

at olivier.guitta@henryjacksonsociety.org

This essay consists of parts that were

published as independent articles.

Part 1 was published September 2, 2013 in the

Weekly Standard, Volume 17, No 48 and is archived at

http://www.weeklystandard.com/author/olivier-guitta.

Part 2 was published in the Weekly Standard

and is archived at

http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/algeria-and-its-islamists_745834.html.

Part 3 was published August 5, 2013 in the

Washington Examiner and is archived at

http://washingtonexaminer.com/rising-stakes-for-the-us-in-mali/article/2533894.

Part 4 was published July 26, 2013 in the

National Post and is archived at

http://fullcomment.nationalpost.com/2013/07/26/olivier-guitta-europes-half-way-ban-on-hezbollah-wont-please-anybody/.