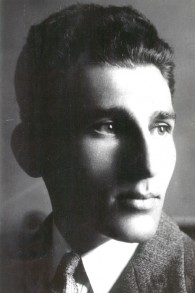

Avraham 'Yair' Stern, commander of the Lehi, was killed 70 years ago this week (photo: courtesy Lehi Museum)

THINK-ISRAEL |

Seventy years ago this week, on the 25th of the Hebrew month of Shvat, three British officers burst into a small apartment in south Tel Aviv, in the now trendy neighborhood of Florentin, and searched the flat for the most wanted man in Palestine. He was a Polish-born doctoral student of Greek poetry, a scholar of Eros from the Hebrew University, a melancholy romantic by the name of Avraham Stern who had left the University of Florence in Italy and returned to the land of Israel in order to declare war on the British Empire.

They didn't find him at first, but a wet shaving brush in the apartment of an unmarried woman encouraged them to look further, and when Assistant Superintendent Jeffrey Morton thrust a hand deep into a wooden closet through a thicket of dresses, he touched flesh. Stern was pulled out into the light and shot twice. The British officers contended a struggle had ensued; the faithful members of the underground group Stern headed have always said he was executed on the floor of the apartment.

Either way, death did not come as a surprise. In 1934 he wrote: "Let us greet him [the redeemer of Zion]: let our blood be a red carpet in the streets, and on this carpet, our minds shall be like white lilies."

Stern, whose writing was filled with death and the undying glory of valor, was intensely revered by a smattering of followers and widely detested by the majority of Jews in Palestine. He had, after all, advocated for a deal with Nazi Germany, arguing that the Jews in the land of Israel, under the boot of the British, should seek "the least of all evils" and make a pact with the enemies of their enemies, the Nazis, believing that he could oust the British from Palestine and help the Nazis rid Europe of its Jewish presence by moving them to the Hebrew state.

This was in January 1941 and virtually no one agreed with him. Thirteen months later he was dead.

And yet in modern-day Israel, 70 years after his death, there has been a stamp issued in his honor and a town — Kochav Ya'ir — that bears his name and hundreds of teenagers that flock to his grave every year, swearing their allegiance to an ideal of sacrifice largely absent among the majority of Israelis.

The shift has certainly come as a shock to his son. Ya'ir Stern — who was given his father's underground name, Ya'ir, in honor of Elazar Ben Ya'ir, the leader of the besieged Jewish rebels on Masada — was born five months after Avraham's death. He grew up believing that his father was "away in America."

"On the 29th of November 1947, after the UN vote, there was dancing everywhere, people in the streets," Stern recalled on Monday in a phone conversation. "I turned to my mother and asked why everyone was so happy," he said. She told her five-and-a-half-year-old son that the state of Israel had been founded and that his father was dead, killed in the struggle to oust the British from the land of Israel.

"That moment will stay with me forever," he said. "The clashing of those two worlds, the realization that I had no father, the lie that they had told me — I could easily have come out insane."

Stern, a respected broadcast journalist who recently made a documentary film about his father, grew up proud and vengeful, seriously contemplating killing the police officers who had shot his father, but also alone. "We were wiped out, unwanted. My mother didn't have bread to feed us. My father was not recognized as someone who had fallen in the service of the state. She couldn't get a job."

At this year's ceremony, with raindrops falling hard against the smooth marble gravestones at the Nahalat Yitzhak cemetery in suburban Givatayim in central Israel, the man everyone called Ya'ir was eulogized by the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv, Israel Prize winner Rabbi Meir Yisrael Lau, and one of the wreaths laid on his grave was from the Labor-led Haganah, the archenemies of Stern's Lehi revisionists.

"That's a new phenomenon," said Stern of the Haganah tribute: "maybe three years old."

But the large turnout is not. The old timers, the eternally faithful, have always come, Stern said, but the number of teens who attend the ceremony has been steadily increasing.

A religious university student of business management and geography, Yehudah Oren, said he has been coming for years. Asked what it is that draws him to the man, he pulled from his backpack a worn copy of Stern's poetry collection, "In Thy Blood Shalt Thou Live Forever," and found the verse he wanted. It was not one of Stern's greater turns of phrase, something about "the root of evil" being in that we remain "enslaved."

"Too often we still see ourselves as un-free," Oren said. "There is something very Diaspora-like about it."

Aliza Greenberg, a poet in her own right and wife of the late poet Uri Zvi Greenberg, sat primly beneath a tree by the side of the rock that marks his grave. Her silver hair was drawn into a tight braid and she spoke softly when describing her decision to join the Lehi, or Stern Gang, as it is sometimes known in English. "I saw his mugshot in the papers, the price they put on his head, and I knew I wanted to join his struggle. He burnt himself for the land of Israel."

Rachel Avnon, who joined the Lehi at age 16 in 1941 back when "Ya'ir" was still alive, and who was known by the call name "Carmela," emphatically agreed with the sentiment. "It was the Jews who hunted him," she said.

Curiously, government participation was weak. Neither Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose oldest son is named Ya'ir, nor Dan Meridor nor Benny Begin nor Limor Livnat, all of whom had parents in one of the branches of the underground, was in attendance. Ofir Akunis, an MK who represents the young wing of the Likud party but is not a member of the cabinet, laid the government wreath on the grave.

Finally, Psalms were read — Rabbi Lau chose a verse portraying King David on the run from his own son, Absalom — and then Shulamit Livnat, the mother of Minister of Culture and Sport Limor Livnat, began singing the Lehi anthem that "Ya'ir" wrote in Nebi Musa in 1932.

Her voice was full of vigor and young and old all joined in: "Unknown soldiers are we, without uniform. And around us fear and the shadow of death. We have all been drafted for life. Only death will discharge us from our ranks."

Stern, who was buried in secret, in the presence of only three people, has that final line etched onto his tombstone.

Mitch Ginsburg, a graduate of Brown University and a veteran

of the IDF's Paratroop Recon Unit, is the Times of Israel military correspondent. He has reported for The Jerusalem Report, the Forward, the Wall Street Journal and WRNI among others and has translated several works of fiction and non-fiction.

This article appeared

February 20, 2012 in the Times of Israel

(http://www.timesofisrael.com/a-rebel-remembered/). "The Times of

Israel is a Jerusalem-based online newspaper founded in 2012 to

document developments in Israel, the Middle East and around the Jewish

world."