THINK-ISRAEL |

October 31st marks the anniversary of the official end of the Sinai and Palestine Campaigns in the Middle Eastern Theatre during World War I. The British Egyptian Expeditionary Force was led by Field Marshal Edmund Allenby. He is rightly regarded as a hero of the British Empire. However, he is not a hero of the Jewish people. Far from it. Yet a major thoroughfare in Tel Aviv, Allenby Street, is named in his honor. This is an error long overdue for correction.

Field Marshal Allenby stood at the head of the British military administration that governed Palestine for roughly two years. Unfortunately, that first administration set the precedent and the tone for all subsequent administrations, which is why, in 1923, three years after Allenby had been replaced, Moshe Glickson, freshly minted editor of Ha'aretz, protested against "the insult and the deprivation of rights to which we are exposed in our historic homeland, against the crude contempt towards our vital interests, which have become the established system of the Palestine government."

Anti-Semitism pervaded Allenby's General Headquarters. This expressed itself in the denigration of members of the Jewish Legion, who were persecuted whenever they left the camp. The commander of the Legion, Lt.-Colonel John Henry Patterson, described the situation in 1919:

"Certain areas were placed out of bounds to 'Jewish soldiers' but not to men in other battalions. Jewish soldiers were so molested by the military police that the only way they could enjoy a peaceful walk outside camp limits was by removing their Fusilier badges and substituting others which they kept conveniently in their pockets for the purpose. They found that by adopting this method they were never interfered with by the Military Police."

Orders to harass and demoralize Jewish Legionnaires came from General Headquarters. Shmuel Katz, in Lone Wolf: A Biography of Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky writes:

Anti-Semitic behavior filtered down from the heights of G.H.Q. into the rank and file ... Patterson records the case of a British officer who, after spending a year at G.H.Q., was seconded to his staff in the Thirty-eighth. There he made insulting remarks to a Jewish officer. When he was forced by the brigadier to apologize to his victim he burst out: 'I don't like Jews. The Jews are not liked at G.H.Q. and you know it, sir.'...

Allenby — contrary to the widespread view — knew of the charges [of anti-Semitism], which were specific. Second, his failure to investigate them compels the conclusion that he was not appalled at the idea of anti-Semitism in his administration and under his army command. This implication is considerably strengthened by his reaction to Jabotinsky's letter [concerning anti-Semitic acts by the administration]. That letter was couched in language that could leave no doubt as to the severity of the charge and the strong feelings of those who voiced it. He then simply used his military authority to ignore the accusations — and to punish the accuser. It is not unfair to suggest that this revelation should be taken into account in assessing Allenby's personal role in the unhappy events of his period of office.

It's important to note that if Allenby was not himself anti-Semitic, his complaisance in the face of anti-Semitism was ungrateful to say the least. Not only did the Jewish Legion perform exemplary service, but Allenby received critical help from the NILI organization, an underground intelligence network set up by the Jewish agronomist Aaron Aaronsohn. It was Aaronsohn who came up with the plan to break the deadlock before Gaza by outflanking the city and attacking Beersheba, and made the plan possible by providing indispensable intelligence, saving an estimated 40,000 British lives.

The behavior of the British administration eventually led to bloodshed. British officials actively encouraged Arab violence, believing violence would convince Whitehall to revise its pro-Jewish policy. When Vladimir Jabotinsky and his band of defenders repulsed Arab rioters in 1920, they were blamed, promptly arrested and tried by a kangaroo court. Jabotinsky was sentenced to 15 years penal servitude and the others to three years imprisonment for possession of firearms and for taking action to protect the Jews of Jerusalem. These sentences were later commuted.

At the time, however, Allenby upheld the charges and helped to whitewash his administration's outrageous behavior both during the attacks and during the trial of Jabotinsky and his men. One may rightly ask why the name of Allenby Street was not changed then. Well, there was an attempt. In Lone Wolf, Shmuel relates:

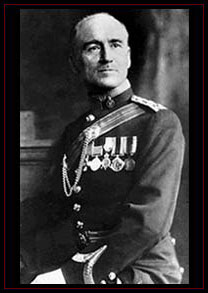

Col. John Henry Patterson

Col. John Henry Patterson

One of the leaders of Hapoel Hatzair, Yosef Aharonovitz, proposed to the Tel Aviv municipality that the name of Allenby Road be changed to Jabotinsky Road. The municipality refused. Aharonovitz went out with a group of young people one night and replaced the street signs. Next day municipal workers restored the original signs; that night they were again replaced. This went on for several days. The story went around that Colonel Storrs, coming on a visit one night to a friend who lived in Allenby Street, was driven around for half an hour while his driver searched in vain for the address. He finally learned that the street described to him by passers-by as Jabotinsky Street was in fact the one he was looking for.

The Jews could be forgiven at first for naming a street after Allenby. It was November, 1918. Allenby had just conquered Palestine from the Turks — hardly a pro-Jewish bunch — and Allenby had yet to preside over the many injustices the Jewish community would be subject to under his administration. By 1920, as Yosef Aharonovitz recognized, Allenby did not deserve a street named after him. There's even less excuse for it today. Indeed, changing the street's name is a matter of honor.

If Tel-Aviv's municipality has trouble coming up with a new name, we suggest naming it after another British officer, the Jewish Legion's commander Lt.-Col. Patterson. There is a street named after him in Israel — in the German Colony in Jerusalem. As far as we're aware, there is no street in Tel-Aviv named in his honor. He deserves a big one. If ever there was a heaven-sent Christian supporter of the Jews, Patterson was it. As Shmuel writes:

An Irish Protestant, he had, it so happened, from his boyhood, studied, out of choice, the history of the Jews, their laws and customs; and spent a great part of his leisure hours poring over the Bible.

Patterson wrote, "As a boy, I eagerly devoured the records of the glorious deeds of Jewish military captains such as Joshua, Joab, Gideon and Judas Maccabaeus." At this writing, the Jewish American Society for Historical Preservation is making an effort to bring Patterson and his wife, currently buried in Los Angeles, to Israel. That would make a propitious moment for a renaming. "Never in Jewish history has there been in our midst a Christian friend of his penetration and devotion," Jabotinsky said.

Patterson paid for that devotion. For identifying with the Zionist cause, he was passed over for promotion. He entered World War I as a lieutenant-colonel and he left it as a lieutenant-colonel.

The Jews should make it clear that, in their book, lieutenant-colonel ranks higher than field marshal.

David Isaac is editor of the Shmuel Katz website:

www.shmuelkatz.com. Contact him with questions or comments at

david_isaac@shmuelkatz.com This article was published on the website

and is archived at

http://shmuelkatz.com/wordpress/?p=812