| THINK-ISRAEL |

| HOME | Featured Stories | Subscribe | Quotes | Background Information | News On The Web | Archive |

|

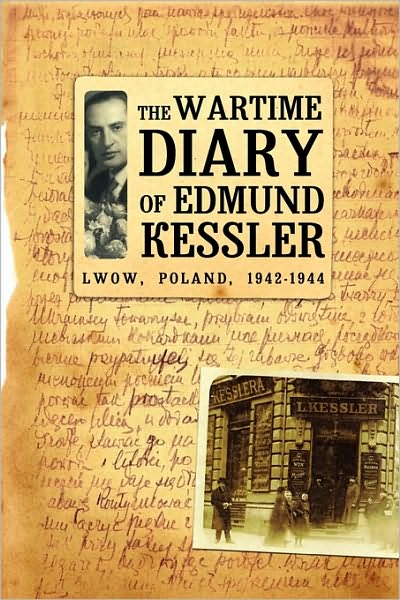

The Wartime Diary of Edmund Kessler. Lwow, Poland, 1942-1944. Edited by Renata Kessler. Introduction by Antony Polonsky Boston: Academic Studies Press February 24, 2010 English; 165pp ISBN-10: 1934843997 ISBN-13: 978-1934843994 |

This is a rather extraordinary little book. Largely the product of years of research, travel, and careful stitching together of details and contributions by Renata Kessler, the heart of this volume is the wartime diary of her father, and a set of his poems (as well as one possibly by his wife Fryderyka), both written in German-occupied Lwów (Lemberg, Lvov) in 1942-1944, when almost the entire Jewish population of the city was murdered by the Nazis and their local collaborators.

The diary takes up a mere 32 pages, and the poems another 33. The rest of the text consists of several introductions, notably by Leon Wells, himself a survivor Lwów and the notorious Janowska camp built in its outskirts, and author of the important memoir, The Janowska Road; by the distinguished historian of Polish Jewry, Antony Polonsky; by Renata Kessler, and by her father. Kessler's wartime writings are followed by a remarkable account by Kazimierz Kalwinski, the last surviving son of Katarzyna and Wojciech Kalwinski, who sheltered 24 Jews in a bunker under their pig shed in the last two years of the German occupation, among whom were Edmund and Fryderyka, as well as Leon Wells. The volume ends with several reflections, of which the most important is Renata Kessler's account of her search for her parents' fate and, as she sees it, also eventually for her own identity.

What makes this book so remarkable is precisely its eclectic nature and the contradictions between the various perspectives, recollections, and interpretations of the nature of the event. Edmund Kessler's own diary, the majority of which is devoted to the early days of the German occupation, beginning on June 30, 1941, is a detached, relentless and searing account of almost fantastic violence. Kessler carefully reconstructs the manner in which such violence quickly accelerates from humiliation and beatings to torture and murder, as city's gentile population discovers that there is a license to kill Jews. Once such permission is given, one discovers that "the indifference of man to man is beyond belief." First, the German military police, "tall, muscular, well armed, " and "escorted by the Ukrainian rabble, vent their bestiality, making rude jokes," ordering Jews on the street "to bow and take their hats off," after which "they are slapped in the face and kicked." Local Ukrainian citizens, obviously delighted with the removal of Soviet rule by the conquering Germans, come out to the streets decked in their "holiday cloths with blue and yellow ribbons — their national colors — pinned on their chests." Initially, remarks Kessler, the city's upstanding citizens "gaze at these vicious games, taken aback by their crudity."

To stop an elderly man peacefully walking in the street and then to force him to stand at attention while slamming his face for no reason and without pity, is something one has to learn. A diligent student soon masters the game on his own, his peasant greed bidding him to combine amusement with practicality. What would be simpler than to seize the opportunity to grab a watch or extract a wallet? After all, the victim is defenseless and there is not even a question of anyone intervening (p. 33).

This is an important observation at the very outset of Kessler's diary. Much has been written on the extent of local participation in the Holocaust, and recriminations about violent antisemitism by such groups as Ukrainians, Poles, or Lithuanians, have been confronted with arguments about Jewish collaboration with Soviet rule in the previous two years of 1939-41, as well as numerous documented cases of gentile rescue of Jews. As Kessler's diary shows, and as other accounts in this book, especially that by Kazimierz Kalwinski, amply demonstrate, in reality such distinctions did not always operate as subsequent observers and historians would like to believe. Violence against Jews could be propelled by antisemitism, but just as much by greed and opportunity; observing the dehumanization of a group often leads to a progressive, indeed quite rapid lifting of moral and ethical constraints. At the same time, antisemitic sentiments did not always curtail the moral urge to help the defenseless even at great risk to one's own life.

These mechanisms of human behavior were triggered by the overwhelming presence of the German occupation and the growing realization that the new rulers were determined to use, abuse, and ultimately murder the Jews. But the specifics of how, and how quickly, this awareness translates in mob violence are described succinctly and insightfully in Kessler's terrifying text. Here, as in much of the rest of the territories occupied by the Germans in the initial phases of "Barbarossa," the invasion of the Soviet Union, murders committed by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, before retreating to the east, were ascribed to the Jews. As Kessler notes, "the Ukrainian mob, encouraged by the behavior of the Germans, is further prodded by rumors spread about the bestial tortures Jews supposedly inflicted on arrested political prisoners" (p. 34).

Yet another element allows the violence to spiral out of control. The Metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church in Lwów, Andrey Sheptyskyi (Andrzej Szeptycki), subsequently became known for his rescue of Jews and condemnation of Nazi genocidal policies and Ukrainian complicity. Yet according to Kessler, this charismatic religious leader's initial response was quite different. Thus he writes that during those early days,

The Ukrainian archbishop preaches a sermon in which, instead of calming the excited mood and taming their barbarous instincts, he demagogically incites the mobs, and in the name of their sacred religion, calling upon the population to retaliate against the Jews for their supposed bestial murder of political prisoners, even though these prisoners included some Jews too (p. 34).

Given this additional spiritual and moral support, all hell broke loose in the city. "A fanatic mob orgy of bloodshed and pillage began." And yet, as Kessler insightfully remarks, "it took place according to a certain system," whereby "the orchestrators... were the Germans. It was they who decided when to begin the pogrom, when to stop it, and how long to torture the victims." Indeed, the Germans "act capriciously toward their Ukrainian subordinates, even beating them when they are slow or overzealous in carrying out orders. They thus emphasize that they are the masters while the native, Ukrainians and Poles exist merely to carry out their commands" (pp. 34-5). Nevertheless, it is Ukrainian militiamen, "abundantly equipped with torture instruments — iron-shod clubs, sticks, shovels, hammers, hatchets, rubber nightsticks, and knuckle-dusters," Who perpetrate much of the violence. As Kessler observes, "the sight of blood does not weaken the lust to kill, on the contrary, it stimulates it," while "the public enjoys gaping at this spectacle, at this martyring of innocent people." Although, according to Kessler, "rarely does someone cast a disapproving glance at the assassins or reacts with pity or disgust," there are nevertheless "instances of individuals who actively defend a publicly beaten and humiliated woman or warn a Jewish passerby against the death waiting for him at the next step." When "someone loudly protests in defense of the bestially beaten Jews or even puts up an active resistance to his assailants... he is quickly silenced and called a stooge for the Jews." But such courageous expressions of empathy and humanity are, notes Kessler, "isolated instances" (p. 35).

The account of this early pogrom, in which Jewish citizens of Lwów were forced to exhume and wash the bodies of murdered political prisoners, and were then beaten to death or shot in large numbers, is as harrowing as it is detailed. Despite its relentless horror, it should be read by anyone who wishes to understand how the Holocaust unfolded in these regions of Eastern Europe. Kessler also makes a strong point about Jewish responses to this violence, noting, "the Jews generally behave passively... with a dumb resignation." They "seek no explanation" for the violence, for "they know it is sufficient that they are Jews." Attempts to bribe the perpetrators were largely ineffective. When the chief rabbi of the city "proceeds to visit the head of the Ukrainian church with a request for help and intervention," according to Kessler "he is received coolly and indifferently... The Metropolitan does not intend to intervene with the authorities in defense of the Jews." upon returning to his home, the rabbi was beaten by the militia and dragged to one of the prisons (pp. 36-7).

The speed with which violence became ubiquitous and an entire part of the population was seen as fair game was quite astonishing. It reminds one that in these parts of Europe, what we call the Holocaust combined with deadly ethnic riots, in which one part of the population violently turned against another. The presence of the Germans made that possible, but the dynamics of the violence had potent local components. As the Jews were being led in a "nightmarish procession" to the prisons, looking "like ghosts, blood trickling from their wounds... tattered masses... under the supervision of German soldiers, police, and Ukrainian militia... in the sight of crowds lining the streets," this "pitiful procession" was "jeered by the crowds... Little children spit at the sight of the Jews barely dragging themselves, as their elders set the example, as they insult, mock, and hit the victims" (p. 37).

This public spectacle of violence continued when the Jews arrived in the prisons. "The crowds clustered around the gate... hurl curses and stones at each entering group of Jews." Once they exhumed the murdered prisoners, the Jews were forced to dig mass graves, all the while being humiliated, beaten, and often eventually shot. The others "stand for hours in the summer heat, fainting from hunger and thirst, awaiting their execution as salvation. They mechanically bury those already shot, envying these still warm corpses their martyrdom... Some bodies are still quivering and have not yet completely expired their last breath... The bodies disappear under the earth without a trace or remembrance. No one weeps for them, no one mourns." Indeed, writes Kessler, "the Ukrainian servants of the Germans dishonor these corpses, kick them, and spit on them, but not before searching them thoroughly for anything of value."

And "despite the duration of the execution, the public's enthusiasm does not wane. The onlookers encourage them with shouts to become even more brutal. What ensues is competition of hitting the victims and kicking the corpses. Their crescendo of curses and shots silence the death rattle of the dying on this devilish day of slaughter." Eventually, even the Germans exhausted themselves physically, as well as morally (pp. 38-40).

These are very important passages. While the diary goes on to describe many other horrors, the account of the first pogrom in Lwów provides crucial insight into the complex, increasingly violent, and ultimately murderous interethnic relations in Eastern Europe, and especially in Eastern Galicia, during the German occupation. Generalizing assertions that under the Soviet and German occupations all the inhabits if these regions became equally victims of murderous totalitarian regimes seem far too simplistic in light of Kessler's account (and many other mostly unpublished eyewitness reports). The festive atmosphere in which one ethnic group observed and participated in the brutalization of another indicates the extent to which victimhood is an all too sweeping category and totalitarian rule a far too vague catch phrase for the complexity, and sheer, terrifying inhumanity, of events as viewed and experienced by the various protagonists on the ground.

Kessler writes in a detached manner, as if he were observing events from afar, chronicling them rather than being subjected to them. There is an eerie quality to the diary because we know that he was, in fact, right there in the midst of all the blood and gore, an assimilated, middle class and middle aged Jewish citizen, who suddenly found himself in hell on earth. For this reason, the poems that follow the diary provide another chilling, and very different layer of experience and expression. Here all detachment is gone. Rather than chronicling the events, the poems provide glimpses of psychological agony, ranging from horror at the extent of the destruction to the enforced intimacy of hiding underground in filth and endless fear. This can be seen in the following extracts from two of the poems:

The ghetto, the Lwow Ghetto, is burning.

Our people drowning in rivers of blood.

Our blood is streaming from the mouths and ears of the victims,

Blood which the earth has massively absorbed, Blood which fertilizes the earth.

Golden sheaves of flames rise to the skies.

The azure blue of the heavens turns red,

The earth joins with the sky in a sea of fire and blood (p. 73)In our cellar hole,

In the blackness of existence,

We live broken and humiliated,

Awaiting rescue. Bodies heaped together, Legs bent,

Pale, chalk-white faces,

Animals, no longer human.

Eyes staring vacantly,

We lie in a row, Forced into mutual embrace...

At the brink of human existence,

We lead a subterranean life. Because

Without this shelter Death's choking grip awaits us.

This second poem leads us to the other, and apparently contradictory extreme of the book. For Edmund Kessler, his wife, and 22 other Jews were saved from certain murder by the heroic acts of an entire Polish family, who hid and fed them for almost two years. The account of this rescue by Kazimierz Kalwinski, the last remaining son of the family, written over five decades later, is remarkable for its insistence on a detailed reconstruction of the difficulties and hazards of putting up and hiding such a large number of people. The Kalwinskis needed great courage, resourcefulness, cooperation, and, not least, luck. This case reveals both that there were gentiles, Ukrainians and (more likely in this region) Poles who came to the rescue and, no less important, that it was in fact possible, though extremely risky, to save Jews.

The account is also important because it unintentionally reveals that those who made such tremendous efforts to rescue others during the war, and who, in many ways, remained inextricably tied to this supreme act of altruism for decades after the war, paying the price and reaping the profits of their actions, might well have embarked on this path imbued with the same antisemitic sentiments and prejudices that characterized much of their contemporary environment. Thus, in the brief historical background that Kalwinski provides for his readers, he speaks with obvious rage about the manner in which "poor Jews," who comprised "the biggest group" of their coreligionists in the area, and were consequently "most susceptible to communist propaganda," collaborated with the Soviets when they marched into Galicia in September 1939: "This is how they thanked Poland for accepting their ancestors centuries before." As a result of denunciations by such young communist Jews, "many Poles and wealthy Jews were exiled to Siberia" (pp. 106-7).

The refrain of the betrayal of Poland by its Jews, attributing to the majority Jewish population of the land sentiments actually shared by a small minority made visible merely because of its sudden and temporary influence among the ranks of the Soviet authorities following the annexation, was and remains a main bone of contention in Polish-Jewish relation. Yet the Kalwinskis made no link between their views of working class Jewish conduct and their willingness to save specific Jewish individuals, toward whom they evidently felt no ethnic or religious prejudices. This once prosperous family of farmers suffered greatly from the war, both because of the deprivations of wartime made worse by the fact that they were sheltering so many Jews (which could have gotten them killed had it been discovered), and as a result of the deportation of Poles from Eastern Galicia to what became the postwar Polish State. The family lost its lands and had to rebuild itself in Silesia, a move from which the father clearly never recovered.

What, then, does this complex account of death and survival in German-occupied Lwów tell us about the Holocaust? Most importantly, I would argue, it demonstrates that local conditions largely dictated the manner in which the German genocide of the Jews was perpetrated and experienced. Overviews of the Holocaust tend to focus on the dynamics of organizing a continent-wide genocide by a mighty industrial state with a modern and effective bureaucracy. Studies of Jewish fate in the Shoah often examine conditions in the large ghettos, labor camps, or concentration and extermination camps. Debates about the role of local collaborators, as well as the contentious part played by the Jewish councils and police veer toward ideological, national, and ethnocentric positions, at times evoking similar prejudices to those that were at work during the event.

To be sure, Kessler also makes some bitter statements about the Judenrat and Jewish police in Lwów, which can be found in many other accounts. But what in crucial in his diary is the degree to which it meticulously reconstructs the transformation of a normal society (though one already greatly disrupted by the previous two years of Soviet rule) into one of savage, unrelenting, and murderous dehumanization and violence, in which all citizens become complicit in one way or another, as victims and perpetrators, losers and winners, often changing roles more than once. And, that this slim volume also contains a no less meticulous account of how one family chose to save a number of very specific Jewish individuals simply out of a sense of shared humanity in the face of a world where such sentiments seemed to have been crushed under the jackboots of the Nazis and their numerous collaborators.

This important book is highly recommended to students of World War II, the Holocaust, and Eastern Europe, as well as anyone who wishes to know about the extremes of human savagery and the nobility of the human spirit.

Professor Omer Bartov is considered one of the world's leading authorities on the subject of genocide. He is the author of seven books and the editor of three volumes; his work has been translated into several languages. His most recent book, Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine (Princeton, 2007), examines the politics of memory in Western Ukraine and erasure of both the memory and the few material remains of Jewish culture there.

| HOME | Featured Stories | Subscribe | Quotes | Background Information | News On The Web | Archive |